Whether you’re negotiating with a prospect, client, or potential partner, it can sometimes feel like your life depends on it. One wrong move and it’s all over in a matter of seconds. Thankfully, most sales calls are not life or death situations. However, my guest for this episode number 211, has been on countless calls that were actual life or death situations. His name is Chris Voss and for 24 years he worked as an international hostage negotiator for the FBI. Now he teaches others the high powered negotiation techniques he honed, while literally saving people’s lives.

Chris is the founder of Black Swan Group and the author of the bestselling book on negotiation, Never Split the Difference: Negotiating as if Your Life Depended on it. He’s been featured in TIME, Business Insider, Entrepreneur, Inc., Fast Company, Fortune, The Washington Post, CNN and more. And I have to tell you, this is one of my absolute favorite business books. I’m not kidding.

This episode originally aired on my podcast, Get Yourself Optimized. If you’re not already a listener or subscriber I should say, why aren’t you? There are such incredible guests on that show. Folks like Dave Asprey, JJ Virgin, John Gray, Byron Katie, Phil Town, Harville Hendrix… these are heroes to me and they are incredible people with such knowledge bombs that will change your life. Think of this episode as a little teaser to get you hooked on my Get Yourself Optimized podcast.

Chris’s techniques involve zooming in on tiny pieces of information that can have a massive impact on the outcome of conversation or negotiation, along with other practices like mirroring and tactical empathy. Let me give you one quick example that I use constantly in my email follow-ups with SEO prospects. I asked them a question to elicit a “no” rather than a “yes” answer. For example, “did you decide to take the project in a different direction?” Or how about this one, “did SEO get sidelined for this year? Now people don’t want to say yes because that’s kind of cringe-worthy or embarrassing. So conventional wisdom might tell you to try to elicit a yes from a prospect, but in this case, Chris’s advice is to go for the opposite. And all I gotta say is, it works.

Negotiation is an essential part of every job, not just sales and not just marketing. I promise you this episode will deliver massive value to not just your business, but also to your personal life. Enjoy!

Transcript

Thank you so much for joining me, Chris. What inspired you to write this book about negotiation? Why a book?

It’s the best way to get the word out. Right after I left the FBI, there were people who were advising me that a book had to be done. We wanted to make sure that we had soup to nuts. We had a full system rather than a couple of ideas in 2007-ish and started the company in 2008. We talked for a while. My son and I primarily are at Georgetown and we were beta testing it. We were having people in the business school who had jobs during the day try this stuff out, proof of concept. It’s one thing to think that it applies but it’s another to completely take it out and make sure that it applies. After a few years of doing that, we figured we had it, so we wrote the book.

It’s been such a game-changer for me. I loved it. It changed, for example, the way I send emails and the way I have discussions with prospects. For example, when I send an email, I’m no longer fishing for a yes, I’m fishing for a no. It was really valuable. Instead of asking, “Do you want to set up a call to discuss the proposal?” I’d ask, “Did you change your mind about SEO this year? Are you no longer interested in pursuing an organic search or whatever?” That would inspire more of a response than, “Anything I can help you with?”

“Are you against setting up a call?” or something like that. The two-millimeter shift makes such a big difference. If somebody’s not against it but they’ll say, “No, I’m not against it but I need the following things.” They can give you a straight answer without being handcuffed by the answer.

Let’s talk about some of the key strategies in the book and how they can play out in a marketing context. Let’s say that you’re wanting to move some leads through the sales process or you’re trying to generate some leads from let’s say Facebook ads. What would be some applications of your strategies for negotiation in that context?

It’s slightly adapting the techniques. People make decisions based on avoiding loss more than accomplishing gain. Ask somebody in a general term and we put this in some of our marketing, “Where do you want to be in a year? Are you willing to give that up? Are you now living in the house that you should be living in?” “No, I’m not.” “How are you going to get there? Are you giving your family everything you want to give them? How are you going to get there?” It’s a lot of the same ideas. Get people looking to the future, compare it to the present and then say, “How are you going to get to where you want to be?” It’s helping people think. It is understanding how people make decisions and not trying to override that, but help them make better decisions.

Essentially, you’re stretching the gap between where they’re at, get them into that place of pain where you’re poking at the pain points. Stretch that gap between where they’re at in pain and where they want to be in the ultimate desired state. Do you think that’s another way of putting your strategies into a construct?

It might be perfect for you. Stretching the gap, I’m not sure what that means. We’re trying to get people to compare things.

Negotiating never guarantees anybody success. It's always guaranteeing people the best chance of success. Share on XAccentuate that gap between where they’re at and where they would like to be. If you’re not living in the home that you’d like to be in, what home would you like to be living in and why aren’t you there? Accentuate the contrast between those two states.

You’re talking about making it clearer and clarity too, you’re emphasizing it. People are up in their heads. What are they looking at? How you process things in your head can be astonishing. What’s the difference between an adventure and an ordeal? How do you process that in your head? With the same amount of pain, some people can be inspired by, some people can be delighted by it. Where do you see it going? Where’s it taking you? It’s a feeling thing. I remember the first time I had some intensive ice therapy on my knee. I was almost at the point of saying, “If you don’t get this off of me, I am going to punch you.” Later on, when I knew what was on the other side of the pain, which was immense relief, you put that iceberg on my leg and I’d be delighted because of where I thought it was going. Where we interpret, where anything is going on in our head is demonstrating an adventure, ordeal or a great quest which we’re delighted by. It’s astonishing what people can tolerate depending upon where they think it’s taking them.

Let’s talk about some of the harrowing adventures that you went on in your days with the FBI and how you learned trial by fire about some of these negotiation skills. Give me the most harrowing that was eventually a success, but you are not sure that you were going to get to that.

Harrowing again is in the eye of the beholder. I’m on C-130 flying into Baghdad. That’s standard operating procedures, taking evasive action so it doesn’t get hit by a missile. People would call that harrowing, to me it was an adventure. I can remember the first time we were in Baghdad. We rode in every helicopter that the coalition forces had from Black Hawks to Chinooks to British helicopters. It was hitching a ride, you catch a ride in a helicopter and you fly someplace else. We’re blasting along at rooftop level on a British chopper headed right straight for some power lines. I want to tap the pilot on the shoulder and go like, “I’m seeing something right in front of us. You’ve got to stay low so that we don’t get hit by missiles.” Before we got to the power lines, it basically shot straight up in the air, went over the top of the power lines and dove back down at the ground to get back to the rooftop level. My reaction was, “It’s a hell of a ride.”

Give me an example of a story where the stakes were high and you pulled out of your hat some amazing negotiation techniques that saved the day and saved some lives.

We never guaranteed anybody success. We always guaranteed people the best chance of success. That’s a fine line that everybody has to grasp in their negotiations. You come up with a good process, you’re either not going to make every deal or you’re not going to want to make every deal. We never guaranteed perfection and we always guaranteed the best chance of success. It’s something I learned a lot from two or three people that were mentors who taught me a lot. Gary Noesner was my boss. There’s a TV mini-series out there, Waco. Michael Shannon is the actor that plays Gary in the show. Gary wrote the book, Stalling for Time. Gary taught me, “We don’t guarantee any success. We guarantee the best chance to success.”

Every now and then you pull something out of a hat and sometimes you make it better for somebody else. One of the first cases I worked in the Philippines, a $10 million ransom demand for an American. He’s been held by murderer, rapist, killers and head-choppers. We got them out of that for nothing. We used empathy on these guys and there was a point in time, I can remember one night when I was working a case. I was guiding it from the US, I remember going to bed one night thinking, “I get up in the morning, our American hostage’s head could be separated from his shoulders. Sometime between when I go to bed tonight because they’re on the other side of the world, the other side of the clock, I get up in the morning this guy could be gone.” He wasn’t. We got him through it and he walked away.

We worked on another case in the Philippines at the time. This time it was a criminal lone kidnapper, serial killer. The only one I ever heard of, which I thought we were dealing with the boss and I didn’t realize how literally true that was. The boss is rarely on a phone in a kidnapping like in most business deals, the CEO will not come to the table. The CEO will send people to the table because the CEO doesn’t want to get cornered at the table. He’s a smart CEO. Kidnapping negotiations are exactly the same thing. The terrorists are criminals. We’re talking to the boss. This guy’s ducking responsibility too much in our conversations. The only people that duck responsibility that much is an influential guy who’s calling all the shots and he doesn’t want you to know it.

We rescued that hostage. We collectively, law enforcement, Philippine National Police on their second try. The first time they tried to rescue the hostages, they missed so bad that the kidnapper didn’t even know they’d been out. They conducted a raid that missed horribly. I thought our hostage was going to get killed when that happened. The kidnapper called back the next morning and said, “Where’s my money?” We were shocked, why is this guy not screaming at us because we had a failed raid the night before? We get some more information, probably about a week and a half later and we had a successful raid the second time around. It was some crazy stuff. Some interesting times, I was blessed to have done any of it.

Let’s take the time that you said you used empathy, you paid nothing and got the guy out. I know you’ve got a phrase called tactical empathy. Can you, first of all, define that for our audience?

It’s weapons-grade empathy. It’s militarized empathy. Unfortunately, empathy as a term has become too synonymous with sympathy these days. That was never how it was intended early on. Understanding is not sympathy. Most people think understanding is but it’s not. Understanding is not agreement, is not disagreement. It’s a completely neutral thing. When Stephen Covey said, “Seek first to understand, then be understood,” he didn’t say agree. That word is not there. There are two elements to the reason why we use the term tactical empathy. Number one, we want people to think about it in a new way first. Second, we know so much more about how the brain works. When the term was first coined, we had psychology to guide us.

Psychology did the best they could but they couldn’t see inside the brain, when you see inside of the brain. If I do specific negotiation techniques designed to appeal to your emotions, we can put you in fMRI brain scanner and watch your brain work in very predictable ways. It’s going to happen every single time. We’ve got a lot of hard brain science behind it. This is not the warm and fuzzy sympathy where, “I feel bad for you. I wish you did better.” It’s not that, it’s not sympathy at all. Daniel Goleman calls it cognitive empathy. In his book, Focus, he says there are three kinds of empathy. The third being cognitive empathy, which is completely neutral. Interestingly enough he says, “The type of person who’s best at it are sociopaths because it doesn’t require agreement. It requires clarity of understanding.” Sociopaths are not emotionally involved, that gives them clarity of understanding. When they don’t care how you feel, they want to know how you feel. Then they can understand you and influence you in incredible ways. It’s not sympathy, that’s clarity. Tactical empathy is clarity on where somebody is coming from and then a subsequent influence with that is amazing. It’s the best there is.

My understanding of building relatedness with somebody, which I think empathy and relatedness go hand-in-hand, you climb that wall of context between you and that other person. This analogy I got from Ephraim Olschewski, who’s been on this podcast before. He says, “You climb that invisible wall of context to the other side, to that side where you get to see their world and what their perspective is and you try to convey to them their world and how you get their world. It doesn’t actually count until they feel gotten by you. It doesn’t count if you get them completely and they don’t receive that. They have to feel gotten.”

That’s exactly it. To us, the indicator when the other side feels completely gotten what they’re going to say to you to tell you’re there, is they’re going to look at you and say, “That’s right.” Not, you are right, not anything other than that’s right. When they say, “That’s right,” they’re all in. That’s the indicator. That’s exactly what you were talking about. I agree with that.

Let’s go back to that scenario where you keep the guy alive and you actually get him back by tactical empathy. What was it that made them feel gotten and they decide, “We’re going to let the guy go?”

First of all, they didn’t let him go. He walked away. They became so lapse in their security and they didn’t care anymore. You’re an American who’s sitting out in the mangrove swamps in the Philippines. Since they don’t care, they’re only coming out and checking on him every few days because they’re tired. He’s sitting out there and he thinks to himself, “What am I doing here? They’re going to be back for three more days anyway, I’ve got plenty of time to get out of here,” and he walks away. What we did in the meantime to get in that position was articulating the other side’s position to them. Carl Rogers, an American psychologist from the ‘70s, one of the most influential psychologists in the history of psychology said, “It’s summarizing the other side’s thoughts and feelings.” It’s summarizing. In this particular instance, the terrorists who claimed to be an Islamic group, they’re killers hiding behind an organized religion.

They said, “We’re not holding the American hostage for ransom. We’re holding for war damages for 500 years of oppression, from oppression on the South of the Philippines, from the Spanish, the Japanese to the Americans.” This an important fact because your typical domestic argument, when somebody says to you, “This is going on for years.” Your brother or your sister, “Ever since we were little, you’ve been picking on me, taking my toys away.” Whatever the people are throwing on your face that has been going on for years in their mind. You’re saying to yourself, “What does that have to do with now? That’s ancient history at best. It’s barely related to me.” When you get into that mode, you’re in an arguing mode, the other side wants an argument when they’re making up nonsense, they’re hoping to inflame the situation. We got in the middle of this thing. We’re several months into it. I was coaching a negotiator and I said, “Summarize this crazy guys’ nonsense, summarize it so much. The world according to the terrorist, give him back everything he said and lay it on thick. When you’re doing this, if you don’t feel you’re laying it on thick, you’re not laying it on thick enough.”

Our guy gets on the phone and believe me, the counterpart on the other side is a raping, murdering sociopath. My guy as a coach says, “You’re not asking for ransom. It’s war damages. Five hundred years of oppression, to the Spanish, to the Japanese and to the Americans. Violation of fishing rights, atrocities under Black Jack Pershing in the early 1900s, you’re not Filipinos anyway, you’re Moro. You’re a separate independent Moro homeland, who are currently oppressed by a public government in Manila held up by the most recent colonial power of the Americans.” We threw everything into that summary. My guy gets done and the raping and murdering sociopath on the other end of the phone says, “That’s right.” They go silent for a few moments and my guy says, “Let’s talk again in a few days.” The sociopath says, “Okay.” When that phone call started, there was a $10 million ransom demand on the table. When the phone call end, the $10 million was gone. It never came up again. They lost their focus, they lost their way. The American walks away.

Empathy is powerful. It doesn't necessarily result in an agreement, but it grants clarity. Share on XI’m back in the Philippines, two weeks afterward on another case. I connect back up with my guy and he says, “You’re not going to believe who called me on the phone.” I’m like, “How am I supposed to know who called you on the phone?” He said, “The sociopath, the terrorist.” The terrorist still has an undercover name and still has an undercover phone number. The terrorist calls my guy on the phone after having lost everything in the negotiation and he says, “You’re good at what you do. They should promote you,” which is a sign of respect. It’s in sum and substance saying, “We’re good.” If we see each other again, if I have to deal with you again, if we have to talk again, we’re good. I’ll talk to you. That’s how powerful, even on a sociopath, tactical empathy is a complete game-changer.

Imagine what this can do in the relationship with your significant other.

With anybody, significant other, business counterpart, into the caveman’s brain is this overwhelming desire to be understood. It’s why Covey said, “Seek first to understand, then be understood.” The gentleman you were talking about was talking about climbing a wall and getting across the other side. Whatever communication arena you’re in, whether it’s relationships, counseling or therapy, it doesn’t matter. The overriding desire to be understood is baked into every human brain. It unlocks collaboration in a way like nothing else does.

I remember this process I learned from Imago Couples Therapy that mirrors your tactical empathy a bit and that you seek to understand first. In this case, there’s this very structured process, it’s called the Imago Dialogue. Harville Hendrix came up with it. He wrote the book, Getting the Love You Want. He was on Oprah. Imago is worldwide. It’s a couple’s therapy that’s all over the world. This Imago Dialogue process has a few components. First, you mirror back everything that the person is saying, if you can’t remember it all, you’ve got to stop them. Maybe every couple of sentences you’re stopping them and you’re mirroring back what they said, using their words, not interpreting it and not interjecting your own opinions or comebacks or whatever, only mirroring. After they feel they’ve gotten it all out and you keep asking, “Is there anything more?” You move to summarize and after you’re finished summarizing, you make sure that they feel that’s a good summary, it’s accurate and it’s complete. If it’s not, then they add some other things, you mirror that and so forth. You go on to validating and then finally empathizing. Validating is it makes sense and then empathizing is trying to get behind the feelings of what they are expressing. It’s very powerful and it keeps you out of your head trying to think of comebacks, rationalizations or whatever. It sounds very similar in some respects to the tactical empathy that you described.

A lot of respects because we’re talking about good, solid, connected communication. It builds collaboration.

In the book, you talk about the three types of yeses and this was a big a-ha moment for me because I was looking for yeses. They were either counterfeit yeses or confirmation yeses and not the commitment yes. That’s the one that actually moves the negotiation forward. That distinction was really amazing for me. Could you share some examples of these three different types of yeses? How to do it better, when somebody recognizes the power of the distinctions between these three?

You can be so off based too on a yes question. An example that springs to mind is a gentleman in a networking group that I’m in. He came up to me and he says, “Are good PowerPoints valuable?” He’s trying to confirm that we agree on a certain point. The problem is nobody asks you a confirmation question unless they’re trying to confirm their footing in a direction they want to go. If you try to confirm, it doesn’t matter why, respectfully, politely, you’ve got something in mind.

You’ve got an agenda.

Nobody asks anybody a yes question without some agenda and very few questions can be answered cleanly with a yes all by itself. This guy’s in a networking group. I’ve got a little bit of a relationship with him so I wasn’t gentle with him. I said, “That is a trap. You know good PowerPoints have value. You didn’t ask me how much value. You didn’t ask me whether or not it had value to me. You didn’t ask me how it fit into my business plan. You try to boil all that down.” What he does for a living is he’s a consultant that helps make better PowerPoints. He is genuinely trying to help me because he heard I gave a speech where my PowerPoint could use some tightening up. It was a genuine question from his perspective. He is a good guy not trying to trap me and lead me down a path.

He is good at his craft with tremendous integrity but in this particular instance, a PowerPoint to me at best has minimal value. I’m going to spend more time on something, in any presentation or anything I’m doing, the last thing I’m going to do is make sure I’ve got my fonts right, the words right or the colors right or any of that stuff. Ultimately any presentation I’m going to give, I’m going to go without a PowerPoint entirely. Every single time I’ll work on my PowerPoint, it has less value. He should have asked me, “The PowerPoints have no value.” I could’ve said, “It’s not that they don’t have value. They had a little value for me.” A tiny little shift in a question. It’s such a trap. People ask you genuinely so much they try to confirm in many cases a common ground. The size and importance of that common ground is frequently tiny.

I’m on a telephone with some people that teach meditation and mindfulness. They gave a talk on meditation and mindfulness. I follow them up. We’re both at a TED Woman’s Conference. So much of great negotiation is so in-line with meditation and mindfulness. You talked before about constructing rebuttals. If you’re constructing a rebuttal, you’re not in the moment and meditation is about being in the moment. There’s a lot of overlap there. To truly listen, you’ve got to be in a moment not constructing rebuttals. There’s a massive amount of overlap. I was highly complementary to what they were doing. They want to collaborate on projects. I’ve already said, “We’ve got all this common ground.” We were on a phone and they were saying, “We feel there’s a lot of common ground between what you talk about and what we talk about.”

If I say yes to this, we are going down a bad path because they want to collaborate. I don’t blame them, but I said, “Don’t get me wrong.” If I had been polite and said, “Yes.” I’d ask a question, it’s answered, we spent a massive amount of time on a completely wrong sheet of music. I said, “I’m not in a position to commit to new projects. While there is a lot of overlap between what we talk about, right now that’s a bridge too far.” For them, it was a disappointing conversation, but I had to disappoint them in the conversation, otherwise they would have understandably been misled if I would have answered the questions as asked. A disappointment would have been even bigger on down the line. We’re not in a position to collaborate with somebody to create a whole new product line. We’ve got too much coming at us.

They could have asked you a question that the yes would have conveyed a commitment. Are you interested in collaborating with us at this time? You could say yes or no. They could have fished for confirmation, yes, which is what they did. They’re trying to get agreements that presuppose a bunch of things and then ending up with a hopeful commitment on their end. The counterfeit, yes, which is basically, “I’m going to be polite and I don’t mean when I’m saying the yes.”

A lot of people are trying to be polite, they don’t know how to break the bad news. They’re worried about the relationship. We coached a lot of people in this business negotiations, we coach, “Do not search for the common ground,” because people are always going to be worried about commitment if they admit to the common ground. As a result, they’re not going to give you a clear picture of anything. The great question from them would have been, “What would stand in the way of us developing a product together?” I could’ve said right away, “Not how could we get something but what stands in the way?” You’ve got to know if the obstacles are insurmountable or not. I could have said, “As of right now, we’ve got no time for new projects, if the revenue is not there.”

We do collaborate on new projects into some degree if the minute I pick up the phone the revenues coming in the door. We’ve got so much underway. I heard the sharks on Shark Tank say, “Good idea is worth $20 at best.” There’s no shortage of good ideas. The key is implementation and how long is it going to take us to implement. You can bring the sharks the best idea on the entire planet but without implementation, they’re not interested because they got lots of great ideas. They’re on the verge of producing revenue immediately. If you start over on a new project that’s two years away, I got people that work for me that got bills to pay. I can’t ask them to forgo revenue for two years. They’re not going to be able to make their mortgage payment.

I’ve heard this before that an incredible team with a mediocre idea, it’s easy to get funding for that and that’s going to turn into something incredible. An amazing idea with a mediocre team, that’s going to go here. It could be $1 billion idea but the mediocre team is going to kill it.

It will be lost. It will be gone.

There’s this conventional wisdom that you try and get seven yeses in a sales conversation, in a speech or whatever from the audience. If these wrong yeses, the counterfeit yeses or the confirmation yeses, instead of a commitment yes, when you start small with small commitments and then work your way up, you’re not going to get anything out of that audience in terms of a behavior shift.

The whole small commitment stuff has been so overdone. Maybe there was a point in time that it was a great strategy. I don’t think it ever was but I’d be willing to concede that before it was overdone, maybe it was okay. At this point in time, it’s like your favorite food. Once you’ve overdosed on it so much, if your little kid loves Oreo cookies, your mom wants you to stop eating Oreo cookies, she got to make you eat the whole box. You’re going to never touch them again. The smell of them on your dying day at age 95, if somebody were to say to you, “If you die, I’m going to put Oreo cookies in your coffin with you, you’d probably live because you so hate Oreo cookies.” Once overdosed on something, you get a whiff of it and it’s instant revulsion. We’ve had the yes, small commitment to large commitment thing overdone on us and you get a whiff of it, you’re instantly repelled.

The overriding desire to be understood is baked into every human brain. It unlocks collaboration in a way like nothing else does. Share on XWhat would be an example of one of these repelling small commitments to try and get a large commitment?

Would you like to make more money? Would you like to have more free time? Would you like to travel the world and stay in five-star hotels, travel first class and get paid $25,000 to do all that?

There’s something disingenuous in that whole questioning.

It feels disingenuous. The reality is to become a keynote speaker, you’ll travel the world in first class accommodations, you’ll stay in five-star hotels. They’ll pay a $25,000 for an hour of your time. That will do that but it felt disingenuous. “There’s something important here you’re leaving out. How do you become a keynote speaker?” “You’ve got to work hard for anywhere from three to five years.” “You didn’t tell me that, you left something important out there.” That’s why I felt disingenuous because it’s not adding up in your head, these yes questions and every one of them was perfectly valid and perfectly true but there’s this omission. When you start on small commitment stuff, there’s almost always a glaring omission, which is why people say, “There’s a trap here someplace. It’s going to be big, if I had known what it is, I would’ve said yes to anything. I wouldn’t even have spoken to you if I did know you’re going to Ieave this up.”

Leaving important details out or the omission, is not only disingenuous, it’s also a straight up lie. When you are lying to somebody, that’s pretty easy for you to know that you’re lying to somebody. A lot of people will tell themselves a story that, “I didn’t speak up about it. I knew it was going to be a problem or whatever. I kept that to myself.” Maybe they come to the realization that it was maybe a white lie but it’s blatant, full out lie in my opinion. What do you think?

We come to learn that as adults and you’re right, there are an awful lot of people. There’s a legal term for it. It’s deception by omission, omitting a material fact is a civil penalty or a crime. It is so practiced and I think that people say, “I never said anything that wasn’t true.” We had a witness in a trial in a terrorism trial in New York a long time ago. When we finally figured out what the guy was holding back, he said, “I promised I would tell you the truth, I just never promised I’d tell you all the truth.” We were like, “The judge is not going to buy that. That is not going to fly.” We had another guy, the most masterful I ever heard. We’re trying to figure out where this Uzi came from that ended up in a terrorist safe house. We want to know the sources of the Uzi.

The witness said, “I heard it came from Omar.” He was a master of deception by omission. He said that to us, “I don’t know. I don’t have a great source, I just heard.” A couple of months later we finally said to him, “You told us that it came from Omar. Who did you hear that from?” He said, “Omar.” That’s omitting a material fact who you heard it from. There are a lot of people that they find that an intellectual game, it’s outsmarting somebody, whatever their emotional satisfaction is for doing it, it’s lying. You know the other side’s being deceived that if you know they’re being deceived, then you’re lying.

I first got exposed to the world of negotiation, how much of a science and a discipline it is way back in 1995. I went to this Karrass Seminar on negotiating. Have you heard of this?

Yeah. It was some of the founders and the pioneers of teaching negotiation.

I learned about it from a full-page ad in one of the airline flight magazines. I was like, “I should know this stuff. I’m starting a business. I need to know how to negotiate.” It was actually pretty good. I learned a lot of tactical stuff and techniques but I didn’t learn a lot of strategies. I learned how to lean back in my chair and puff up my cheeks and looked exasperated like a fish. I forget the exact name for this, but it was like a fish expression or whatever that they taught.

They’re teaching you theater.

That would reset the negotiation because they feel, “We’ve gone a little too far. We’ve asked for too much. We better reel this back in.” What do you think about the theatricals or the parlor tricks, is that something that you recommend people learn? Is it smoke and mirrors and it doesn’t get at the heart of the matter?

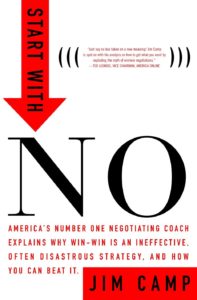

We’ll start with Karrass and we’ll go to theatrics. The ancestry, if you will of our profession, it was inspired by a lot of ideas from a book called Start With No by Jim Camp. It came out about 2002. Camp was a very practical guy. I collaborated with Camp. I did some business with him. He’s since passed on, he’s a great thinker. He went to Karrass and he said, “I love your stuff. I want you to coach me. How much is it to coach me?” The story goes according to Jim’s son and Jim himself that Karrass said, “No, we don’t do that.” Camp’s thought was, “If you don’t have enough faith to coach this and why should I learn from you?” That astonishes me. If you believed in the methodology, you should be willing to coach and put himself on the line with the player. Put yourself on the line. The story goes that Karrass says, “No, we don’t do that.”

That’s quite common. You’ve got a lot of people that are teaching negotiation. I had a conversation one of the major top tier Master’s program, Business University. I said, “This is cool. You’re teaching it. How much coaching do you do?” This person said to me, “No, I would never coach.” I remember thinking to myself, “If the people you’re teaching don’t think you believe in your stuff enough to coach it, that should scare them,” which is Camp got into coaching and consequently, we’re coaching a lot more than I ever thought we would. You should have second thoughts about somebody who will teach you in negotiation but won’t walk through the process with you and help take responsibility for the outcome.

Let’s get forward to what some academics would refer to as strategic umbrage, feigning anger or actually be angry. We talk about it in the book a little bit. I don’t know if we hit it hard enough. It’s a bad idea. Let’s take feigned anger to begin with, that’s lying and we’re against lying. We don’t like lying, integrity, long-term relationships. You shouldn’t engage in a negotiation where the other side won’t be happy with your motivations and where you’re coming from. If they saw everything you did and everywhere you came from, they should because they will eventually anyway, if you have any long-term relationship with them. How are you going to maintain a relationship if you lie? Feigned anger in my view is the equivalent of lying. People talk about it because strategic umbrage in false situations has been demonstrated to help make deals and pretend negotiations. There’s an academic study out there that says strategic umbrage worked but it was taking in under false circumstances.

For an academic study, typically they have to run simulated negotiations so they can control all the factors. The only way you can control all the factors is to give people sides, hand them the script and say, “This is who you are, this is your circumstance, negotiate this.” I have been taught in business school, I know that if I hand somebody a script, they’re going to feel they have to make the deal in one setting and they’re going to allocate 45 minutes to it. They are never going to have to implement the deal ever. They’re not going to have to see each other again in the same relationship. You in business, you’ve got to implement the deal and you have to have a long-term relationship. Anger is a nuclear waste and it poisons relationships. If I get out of you what I want from you with anger, you’re going to see them and it’s going to affect your implementation. It’s going to affect our relationship. Look at Washington DC, you think anger is working well between the Republicans and the Democrats. We got some seething tit for tat going back and forth on both sides. I’m not seeing how that’s making the world a better place.

That’s the fakeness of these outward tactics, the theatrics. Are there any theatrics or ways of positioning your body posture or whatever that are legitimate and do work in your opinion?

Being genuine and being trustworthy works.

What about mirroring and matching? What if somebody is crossing their right leg and so you cross your right leg, is that legitimate, is that manipulative or not an integrity? What do you think?

Are you genuinely in sync or are you doing it because they’re doing it? One is genuine and the other is a lie. At some point of time we start to parse this out, we’re going to get to genuine, disingenuous. If it’s genuine, I’m for it. If it’s disingenuous, that’s another word for lying, which is bad. Some physical mirroring and matching are going to happen if we get into sync. That’s another thing that is so overused that you might genuinely be in sync with me but so many snake oil salesmen had tried that with me, that if I catch you doing it, I will immediately distrust you. When in fact where you may have been coming from may have been legitimate, it’s unfortunately the snake oil salespeople out there have overused this as well. You’ve got to be careful jumping into somebody that something that the snake oil salespeople do.

Good, stable, and connected communication surely builds collaboration. Share on XIt’s the small commitment thing, overdone to the point where it makes you uncomfortable if you even get a whiff of that coming your way.

Every now and then I will find myself genuinely, physically mirroring someplace, someone else and I’ll actually stop myself from doing it. The last thing I want to do is inadvertently look like the hustler or the con artist.

What things do people do in negotiations that inadvertently inflame, break rapport or create a lot of resistance?

The tone of voice can be problematic. You’ve got to be cautious about the tone of voice. Your inner voice is going to betray your outer voice. You have to be careful about it because if you ask me a question and the answer is no. My tone of voice says, even though I didn’t say it, “That was a stupid question.” You’re going to feel stung. If I take the time and I realized I want my no to land softly then I’ll say, “No.” That’s telling you that I’m trying to get what I have to say to land softly and you’re going to appreciate that. We have to be careful whether or not our inner voice betrays our outer voice. That’s one of the main things that has a lot to do with type. There are three basic types. I’m a natural born assertive and I am one where I got to watch my inner voice betraying you in a way that you feel slapped around. Even though I haven’t said anything, my tone of voice can easily be bad.

If somebody wants to dig a lot deeper, of course, they need to read your book. Your book is amazing. I constantly recommend it. I have oftentimes said to people, not only do I recommend it but is the best business book I have read in the last several years.

Thank you very much. It was a team effort. Tahl Raz is a brilliant writer. My son was heavily involved. He’s uncredited. Thank God he works in my company with me, otherwise, he’d be suing me.

There's no shortage of good ideas. The key is implementation and how long is it going to take us to implement. Share on XWhat if people wanted to take it to a whole other level beyond reading the book? They wanted to get trained by you and your team, maybe even coach, do you offer coaching?

We offer it all and the gateway to everything that we have actually. We put out a once a week newsletter. It’s short and sweet. It comes out on Tuesday mornings. It is a short and concise article plus it’s the gateway to our website. The newsletters called The Edge. It’s free. It’s a reasonable price. You don’t have to mortgage to get it. The simplest way to sign up for the newsletter is to send a text message, text to sign up function. The message you send is FBIEmpathy and send to 22828. You’ll get a message back to sign up and you’ll get a free negotiation concise lesson once a week. Plus, it will take you to our website. There are training announcements in there.

The website is BlackSwanLtd.com. The quickest way to get there is via the newsletter. We’ve got a fair amount of content out there that’s free. We’ve got a YouTube channel, the newsletter or the website will take you there. A lot of people are getting a long way off the free content that we put out there. You got some high stakes stuff coming at you hard, we’ll coach you. We’re not cheap but the crazy thing about our coaching is we don’t coach people for long. We rarely coached anybody longer than ten days. We’ll get you to the best possible outcome. We’ve had people struggling with deals for eighteen months. We’ve had it resolved in ten days. The emotional intelligence approach is a great time hack.

You also teach workshops too.

We’ve got one-day workshops. We’re going to have a robust schedule. We’re going to have ten of them all across the country. Wherever you are, we’re going to have a workshop close to you sometime in the near future.

Thank you so much, Chris. This is amazing. I’m privileged to be talking to you. I hope our audience take some action, sign up for your newsletter, buy your book if they haven’t got it and maybe even take one of your workshops and get coached by you. To my audience, take some action and we’ll catch you on the next episode. Take care.

Was that awesome or what? If you enjoyed this episode with Chris Voss, could you take a moment and please give my show a rating or review? I’d really appreciate it. And we’ll catch you on the next episode of Marketing Speak.

Important Links

- Chris Voss

- The Black Swan Group

- YouTube – The Black Swan Group

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On It

- Stalling For Time

- Focus

- Getting the Love You Want

- Start With No

- Get Yourself Optimized

- Dave Asprey – GYO previous episode

- JJ Virgin – GYO previous episode

- John Gray – GYO previous episode

- Byron Katie – GYO previous episode

- Phil Town – GYO previous episode

- Ephraim Olschewski – GYO previous episode

- Harville Hendrix – GYO previous episode

- Chris Voss – Stellar Life Podcast previous episode

- Karrass Seminar

- The Edge – newsletters

- TIME

- Business Insider

- Entrepreneur

- Inc.

- Fast Company

- Fortune

- The Washington Post

- CNN

Your Checklist of Actions to Take

About Chris Voss

Chris Voss is CEO of the Black Swan Group and author of the national best-seller “Never Split The Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On It,” which was named one of the seven best books on negotiation. A 24-year veteran of the FBI, Chris retired as the lead international kidnapping negotiator. Drawing on his experience in high-stakes negotiations, his company specializes in solving business communication problems using hostage negotiation solutions. Their negotiation methodology focuses on discovering the “Black Swans,” small pieces of information that have a huge effect on an outcome. Chris and his team have helped companies secure and close better deals, save money, and solve internal communication problems.

Chris Voss is CEO of the Black Swan Group and author of the national best-seller “Never Split The Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On It,” which was named one of the seven best books on negotiation. A 24-year veteran of the FBI, Chris retired as the lead international kidnapping negotiator. Drawing on his experience in high-stakes negotiations, his company specializes in solving business communication problems using hostage negotiation solutions. Their negotiation methodology focuses on discovering the “Black Swans,” small pieces of information that have a huge effect on an outcome. Chris and his team have helped companies secure and close better deals, save money, and solve internal communication problems.

Chris has been featured in TIME, Business Insider, Entrepreneur, Inc., Fast Company, Fortune, The Washington Post, SUCCESS Magazine, Squawk Box, CNN, ABC News and more.

Hi Stephan,

Podcast Awesomeness. I have Chris’s book which is amazing. I’ve used it along with Jim Camp’s material. My wife who works in a top 4 firm is using it extensively.

It’s so great for emails, texts and of course in speaking with someone live.

Much love and prosperity!

-Tommy Lentsch

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm4704179