Before you step onto a stage to speak, you need to have clarity on two big questions: who your target audience is and what specific problem you solve for them. Once you answer these questions, it’s surprisingly easy to put together a great talk (or webinar, podcast, and so on). It’s when you’re vague and loose with these answers that your talk might meander and not reach anyone.

Pat Quinn didn’t get his start as a professional speaker. Instead, he worked as a professional magician for 10 years before deciding to get a “real” job. He became a public school teacher and taught high school for 12 years, during which time he got a degree in brain research and focused on how adults learn. This combination of experiences means he brings both stagecraft and a deep understanding of audiences to his presentations. Tune in to hear his wisdom and learn how to apply it to your own talks and presentations!

In this Episode

- [01:11] – Pat starts things off by talking about how to be a better speaker, and some of the biggest screw-ups he’s seen.

- [03:59] – We hear about how you can know when you’re on the right track.

- [06:13] – It’s a lot harder to sell someone a solution if you first have to convince them that there’s a problem, Pat points out.

- [11:03] – Stephan explores a connection between what Pat has been saying and something he learned from Neil Strauss.

- [12:55] – Pat digs into the importance of storytelling when you’re speaking, and gives specific examples of how this can work.

- [18:09] – We hear about two types of speakers who nobody wants to listen to or engage with.

- [20:18] – How do you give concrete steps that will help the audience make an improvement without giving away the farm?

- [26:47] – Stephan shares something that he learned early in his career. Pat then points out the importance of getting your audience to remember what you talked to them about.

- [32:09] – Most of the changes that Pat makes with the speakers he works with is shortening, not lengthening, their presentations. He then recommends having a mixture of short-term and long-term solutions.

- [36:43] – The key to getting people to engage with you even though you gave them your best stuff is to include long-term solutions that people need to engage in.

- [39:36] – Pat digs deeper into the role of storytelling in presentations, and explores one of the stories that a lot of people make.

- [43:45] – What Pat has been saying reminds Stephan of Matt Church’s “pink sheets.”

- [45:46] – What does Pat tell people who take the approach of awkwardly splitting a presentation into a teaching section and selling section?

- [52:23] – The process Pat has been describing is called “seeding” or “embedding,” he explains.

- [58:33] – Pat talks about whether he has a go-to strategy for the next step, such as inviting people to a call. He then shares a specific example of a story that everyone can relate to and teaches the point he wants to make.

- [67:38] – How can people reach out with Pat to work with him or learn more?

Transcript

Public speaking is arguably your most important skill. For me, it drove eight figures in revenue over the last 23 years. It was the biggest revenue-generating activity–bar none. If you wanna up-level your public speaking, this episode number 134 is a must. Our guest today is Pat Quinn. He’s a presentation coach with 20 years of experience helping the best speakers in the world improve their effectiveness. Pat, it’s great to have you on the show.

It’s a pleasure to be here. Thanks for the opportunity.

Let’s talk about how to be a better speaker. I think the best way to start when you talk about how to be a better speaker is–what are the biggest screw-ups that you’ve seen in regards to not doing a good job.

This happens even before you step onto the stage or start your webinar. When I coach speakers, it’s not just on a stage. It’s also on all the online ways you can be on through podcast and webinars. One of the mistakes that speakers make is not to have clarity on two big questions: Who is your target audience and what problem do you solve for them? What I find when I’m working with a speaker is if you have total clarity on these two things, who are you trying to reach and what problem do you solve for them? It’s actually pretty easy to put together a great presentation, a great webinar, or a great podcast. But when you’re mushy about this, when you say, “My target audience is every living human being in the world, and the problem I solve for them is improve their life,” that’s not specific enough, it’s not tight enough, it’s not directive enough, and that’s when I find that you put together a presentation that meanders, a presentation that’s all over the board, and a presentation that—although it’s directed to everyone—actually reaches no one. In this clarity question, the second question is harder to answer. What problem do you solve for them? Most of the time when I ask people who are running their own business trying to be helpful to other people, and I ask, “What problem do you solve for them?” They actually list a solution. When I say, “What problem do you solve for them,” they say, “Well, I change their mindset.” I say, “Well, that’s not a problem. That’s a solution.” When you think of the problem you solve as a solution instead of a problem, what happens is you put it in your language. As service providers and solution providers, we think, eat, and sleep this stuff every single day, which has a speaking or language of our own solutions. What some of us have lost over the years of helping people is the very language that our clients are using to describe the problem. If you don’t know how to describe the problem in the language of your client, you’re in trouble. All great speaking is really taking the client from where they are to where they need to be. But to do that, you have to start in their language using their words. Total clarity on who you are trying to serve, who your target audience is, and what problem you solve for them is the first step of the great presentation and if you don’t have it, you’re going to be in trouble.

Yeah, it seems in order to connect with their audience, whether it’s a room full of people or it’s just one person one-on-one in a sales environment, you need to connect with them and speak to them in a language that resonates with them in a way that they care and maybe say, “Yeah, I had that situation myself.” It’s more of a ‘me too’ or ‘me as well’ instead of a ‘so what.’

Exactly and you know you have this when you say the words and we often help people to figure out these words by looking at surveys that they done with previous clients, when they got started not at the end of the process, and just to have conversations. If I talk to somebody and they say, “I have no idea how they would describe this problem,” because one of the questions I always ask is, “What is your prospect, what is your ideal client lying awake thinking about? When they complain to their friends, what are they complaining to their friends about?” If I get a blank stare I say, “Well go ask 20 of them and write down to the exact words that they say because those are the words you’re going to want to repeat back to them.” You know you have this when you say the words, whether it’s on stage or across the table at Starbucks, and they start nodding vigorously because you have described their problem better than they could describe their problem. When you have that moment where they’re nodding like, “Oh my word, I’ve been feeling this so long, no one has ever put words to it,” you have them. You have them by the neck. You can sell them anything you have. They’ll go on any journey with you because you’ve described their problem better than they’ve described their problem, and that’s really what they want. That’s better than all your benefits, that’s better than all your features, it’s better than all of your bonuses, it’s better than all your price reductions. If they think you understand their problem as well or better than they do, you’ve got them right where you want them. That’s a huge part of the process, whether you’re one-on-one with somebody and every presentation that we put together for people. We leave them with a map of the presentation and that very same map can work in a 5-minute interview and a 60-minute keynote, it can work in front of 1000 people on stage, and it can work across the table at a coffee house just describing what you do to someone else because the process is the same. The process is taking someone from what they’re thinking about now, to what you want them to be thinking about in the future.

Aren’t there multiple types of problems? Isn’t there the known and spoken problem, but then there’s the known but unspoken problem, and then the unknown, unspoken problem that they’re not even aware, they can’t articulate it or they don’t want to articulate, and they don’t even know it exists?

Yes. We think it’s a lot harder to sell someone a solution when you have to first convince them that there’s a problem or first teach them about the problem. One of our mantras in speaking is to sell them what they want and then give them what they need. This is what we’re talking about the very opening of your presentation, you have to be where they are in the known problem that they speak about or haven’t been able to put words to yet but they know it’s a problem. It doesn’t really matter how long the presentation is. Research shows that there’s kind of a ticking clock from the moment you start speaking that people are going to make decisions about you, about how closely to listen, about how much to believe. There’s three things that you have to do in the first five minutes. Anytime you’re up in front of somebody, whether it’s online or offline, you have to be ordinary, you have to be extraordinary, and you have to show your why. Ordinary means I’m just like you. I’ve done what you’ve done, I walked in your shoes, I’ve worried about what you’ve worried about. Extraordinary means I’ve done some things that you haven’t done, I have some experiences you haven’t had, I know some things you don’t know, that’s why you should listen to me. Of course, you should show your why. We all have probably heard speakers who are too extraordinary. They get up on stage and say, “I have a $100 million business. Every time I launch a product, I sell $10 million of it. My list is 175,000 people strong.” At some point, if you’re a startup or you’re somebody who struggles a little bit, you’re listening to that expert saying, “Well, I’m not sure this person can help me.” “They have everything together and I don’t.” You lose audience members if you lean too far that way. But we all have also heard speakers who are too ordinary. They get up and say, “Hey, I’m just like you. I worry about what you worry about, I struggle with what you struggle with, and honestly, my last launch I didn’t sell any of it. My business is going under right now.” At some point, you sit there thinking, “Well, why are you on stage and I’m in the audience? Why did I pay to come here? Why are you getting paid to come here?” You kind of have to walk this tightrope. You have to walk this tightrope where you say, “I’ve been in your shoes. I know what you’re worried about. I walked this path, but here are some other things.” I often open my presentations by saying, “I’m a speaker, I stand up on stage, I go online, webinars, podcasts, and I do just what you do. Now, I didn’t get my start as a professional speaker. I actually got my start as a professional magician. I worked in magic for 10 years and then I realized I need to get a real job, and I decided to become a public school teacher. I taught high school for 12 years and during that time I picked up a degree in brain research, on how adult learners learn.” I really bring two things to the table. A little bit of stagecraft from the years performing magic, and a real understanding of how your audience absorbs new information. When I’m watching a speaker, I’m oftentimes not looking at the speaker. I already know what the speaker looks like. It’s much more important to look at the audience because how the audience receives the information is what really matters. You can stand up and I can teach you tricks to get a standing ovation, but I think if you want to change the world, what you really want is the audience to learn, know, and use your information. That requires a real understanding of how the audience absorbs information. I’m mission-driven. I can teach you how to make more money, but I like to work with people who believe when the audience hears them, they leave better off with the experience–that their life will be better because you heard me speak today. That’s the type of speaker that gets me up in the morning that I absolutely love to work with. In that 90 seconds where I went from being a speaker, to a magician, to a teacher, to a brain research person who understands how adults learn, to being mission-driven–I did three things. I was ordinary just like you. I speak sometimes on stages, or on podcasts, or on webinars. But unlike you, I understand the world of stagecraft and magic, and I understand how adults learn. I showed you my ‘why.’ I’m mission-driven. I’m not just here to make a buck or to show you how to make more money in your conversions—although I can do that—what I’m really here for is to work with speakers who want to change the world and because of confirmation bias, everybody in the audience puts themselves in that category and you’re perfect clients for me. In 90 seconds, I was ordinary, extraordinary, and showed my ‘why.’ In the first five minutes, if you don’t do those three things, you’re going to see it in your conversion rate at the end. You’re going to see it in how closely people listen and how much they want to engage with you after the fact.

That is awesome. There’s so much in there that I love to unpack. One thing that came to my mind almost immediately when you’re talking about being extraordinary is in the world of pick-up, pick-up artists use a lot of acronyms. I learned a little bit of pick-up from Neil Strauss, I was in his mastermind for a number of years. It’s called a DHV, a demonstration of higher value. By the way, listeners, if this at all intrigues you, the world of influence and persuasion is absolutely mastered by pick-up artists and I had one of the world’s greats on–Ross Jeffries was one of my guests on a previous episode. Be sure to check out that episode if this intrigues you. There’s this time when I went microlighting above Victoria Falls in Zambia and it was pretty sketchy, the motor didn’t seem to be that reliable. I’m telling a story about it and I was like, “Wow. Here’s a guy who can afford to go on a trip to Zambia and go on a hang glider type thing with a motor attached and above Victoria Falls.” That’s a demonstration of higher value without having to read off a resume or a bunch of accomplishments. That’s what I was thinking about when you’re describing your story, your weaving in your little DHVs and I loved how you worked in, you mentioned, tricks to get a standing ovation. Some people are into the hacks, into the tricks and stuff and you just threw them a bone while you were being ordinary and extraordinary and showing your ‘why.’ I loved all of that.

Yeah. One of the most effective ways to do those three things in the first five minutes is through storytelling. We want a very specific type of storytelling with our speakers, which is episodic storytelling. Some people tell their bio on the opening sequence of the presentation, whether they just introduced themselves to somebody at a cocktail party or they are on stage giving a big keynote presentation, they tell it in a narrative form like you’re writing a biography about yourself. “I was born in this year in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. I went to this college, and then I did this, and then I did this…” That’s fine but it doesn’t make people want to engage with you further. A much better way to do it is through episodic storytelling which is to take people right into a room with you, right into a moment with you. Sometimes you’ll start with a little, “Good morning. It’s great to be here today.” But sometimes, we like just to dead drop start too where you drop them right in the middle of a story where the very first words out of your mouth are, “It’s two o’clock in the morning and I’m driving across Kentucky and I’m wondering to myself what am I doing here,” and you kind of just take them right into the moment. That really, from the very moment you start the presentation, will engage the audience and really gets people into the story. But doing it through episodic storytelling done correctly, you will have the audience feeling what you feel, hearing what you hear, and if you do it right–smelling what you smell. You would have 100% engagement. One trick that I always give speakers is when you’re filming yourself—a lot of people just put up a phone and film themselves so they can review it or send it off to their coach—is to turn the phone around. You already know what you look like. Turn the phone around and film the audience as you speak. What you’ll be able to do if you do this is you’ll be able to hear your audio so you’ll know where you are in your presentation, but you’ll be able to see how the audience is responding to your presentation. If you do this, at times you’ll see that the audience is totally still, totally silent, and they’re actually leaning into you, and there’s other times when they will lean back, where they’ll look through their programs, where they’ll check their phones, and they’ll be thinking about other things. Those are the times that you should throw out things in your presentation, and the times that they’re leaning in and perfectly still are the things you should keep. It’s almost always episodic storytelling that will get them leaning in and done correctly, they’ll even breathe with you. Many of the speakers I work with are so talented and so good. I’ve been very fortunate enough to work with a number of Olympians, astronauts, and New York Times best-selling authors who can actually get the audience to breathe with them when they’re telling a story like this. One speaker who came to Milwaukee for our two-day story execution workshop was LaVonna Roth. LaVonna told her story, she grew up very poor, which a lot of people try to indicate at the beginning of their presentation what their situation was growing up and she used to start like that, and say “We didn’t have a lot of money when I was growing up,” like a narrator would if they were writing a biography. We had her change that into an episodic story. When she was 14 years old, they got evicted from their apartment and a friend asked them to move in with them or said they can move in with them. They went over there and they said, “Well, we don’t actually have an extra bedroom for you, but we have a chicken coup next to our garage we’re not using anymore. You could stay in there.” She tells now from a first-person viewpoint what it was like as a 14-year old girl to walk into that chicken coup. You see what she sees, you hear what she hears, and you smell what she smells. She realizes this is where she’s going to live for the next six months. I’ve watched her audience respond to her when she tells it like a narrator writing a book, and I’ve watched her audience respond when she takes us into that room with her, and you could hear a pin drop. Every audience member is with her at this moment and when you have that happen, especially at the opening of your presentation, two things happen. The audience is going to listen to the rest of your presentation and buy into it better. But more importantly, the audience is going to want to engage with you further. The primary purpose of any presentation usually isn’t to get a standing ovation. I have people come to me and say, “Can you help me make the audience cry?” I just kind of roll my eyes and another people just want a standing ovation. I think the ultimate goal of most presentations is to get the audience engage with you further, so that they follow up with you and enter your program, buy your product, user your service, engage with me further. An episodic storytelling is your greatest tool to do that. It’s your greatest gift when you can get them in a room with you, feeling what you feel, hearing what you hear–they are going to want to engage with you further.

Yeah, for sure. Many speakers, many regular people are introducing themselves before they start building rapport, interjecting the social proof and the storytelling. “Hi, I’m Stephan Spencer. I’m a three-time author, blah, blah, blah.” Nobody wants to hear that as the first words that come out of your mouth.

That is true. That’s why you want to engage with them a little differently than that. The two other types of speakers that nobody wants to listen to are–first of all, there’s one type of speaker who spends their entire time just describing the problem. I noticed speakers all the time who, when they have 20 minutes on stage, 15 minutes in are still describing the problem and are not offering real solutions. Then they wonder why they’re not getting clients out of that or they’re not getting additional business out of that. We never want you to describe the problem for more than 25% of your time. You have to switch into solutions. I’m sure there’s exceptions to that rule but in most presentations, think about the amount of time you have. You better be out of the problem portion of that and into the solution portion of that by 25% of the way through that time. The other type of speaker that does not get booked very often and the audiences don’t want to engage with are speakers who stick in theory the entire time and only talk about theory. “Theoretically, this is the way it should be. Here’s some information that you really can’t do any with.” If you spend your entire presentation just giving us information and not giving us concrete steps that we can actually do, even if they’re small one, even if they’re short-term, every audience wants to walk away with little concrete steps that they can do the very next day to make a change, to make their life a little bit better. When you have a speaker who does either of those two things, spends the entire time describing the problem or stays only in the theoretical world and never gives me anything that I can actually do the next day, you’re going to find your stages falling away or getting smaller and smaller and smaller. You are also going to find that when you do get those stages, you’re not going to have engagements after the fact. Fewer people are going to join you on this long journey. They may stick with you during the presentation, but you’ll find that there’s less engagement after the presentation.

Yeah, that makes sense. How do you give the concrete steps that will help them make a change, make some improvements the next day or the next week without giving away the farm and kind of whetting their appetites but wanting to spend their money with you and go through your program or hire you as a consultant?

The first thing you have to do is help them realize that they are getting concrete information. After you get through that opening segment where you are ordinary, extraordinary, and show your ‘why,’ it’s really important—sometimes people chuckle when I say this because it sounds like we’re back in high school speech class—that you roadmap your presentation and tell them ahead of time, “I’m going to give you some real concrete things in three areas.” We like presentations, the content portion, the middle portion of a presentation to be broken up into sections. The reason you want it broken up into sections—we recommend three or four sections—is because people can remember three or four things. That’s why phone numbers are broken up into three digits and four digits so that we can remember them. You might have a seven-step process, you might have a 10-step assessment, you might have eight different ways that you help people but in each single presentation and in each single audience, you should either pick the best three or four, or chunk them up so that there are three or four things that they remember. Right after the opening segment, five or six minutes into your presentation, you should say then, “Today, I’m going to talk to you about some very specific things.” Right away we’re moving from abstract into concrete. We’re moving from theory into practice. Then tell them what those three things are going to be. That’s roadmapping and it’s an important part of the process. Here’s a pro-ninja tip for you. When you do the roadmapping of your presentation, mention a time element. Tell them how long you have. “The next 30 minutes I’m going to talk to you about these three things. This, this, and this.” If you don’t do that, and this is true on a one-on-one conversation at Starbucks, and this is true in the biggest keynote events in the world. If you don’t tell them that you know how long this is going to last, about halfway through or three-quarters of the way through your presentation, somebody is going to think, “Hey, I wonder if this person knows how long this is supposed to last?” When they do that, they’re going to look at their phone or look at a clock. All audience behavior is contagious. If one person laughs, everybody laughs. If one person cries, everybody cries. If one person stands up to clap, the rest of the room usually stands up to clap. But when one person looks at their phone, other people look at their phone. When one person looks for a clock, other people look for a clock. All audience behavior is contagious and if you have people thinking three-quarters of the way through, “Does this person really know when this ends because there’s only 10 minutes left and they’re still rolling. They might go on for another hour.” That’s true on one-on-one, too. When you sit down with somebody at Starbucks to hear what they have to hear or what they’re doing or what they’re selling, you usually have in your mind how long this is going to last. At some point, you’re thinking like, “How long am I actually going to be here?” All this can be avoided and we call this interference. Interference is anything that comes between the speaker’s message and the person receiving the message. When you’re thinking of other things, if you think of the human mind it has processing power. If you’re using up processing power, worried about traffic when you leave here, if you’re worried about how long the line is going to be in the bathroom, or if you’re worried about does the speaker know when this presentation is supposed to end because they’re still going and there’s only five minutes left, all of that is taking up bandwidth that could be used on listening to your presentation and thinking about engaging with your further. But you can avoid all of this simply by saying–at this roadmapping portion early in your presentation, “In the next 30 minutes, I’d like to talk to you about this,” and this works even on one-on-one. “I’d like to spend 15 minutes today showing you what I do or showing you how I can help you.” If you just add that time element, “I’d like to spend 15 minutes doing this,” it takes this giant weight off the other person’s shoulder they don’t have to worry about that anymore. I can worry about a lot of other things but I don’t have to worry about if you’re going to keep me here for three hours or if you’re going to go along in this session so I don’t have time to go to the bathroom before the next session or all the other things that people worry about when a speaker goes long. Adding the time element to the roadmapping portion of your presentation is absolutely essential. One last thing you should add during your presentation, be sure to benchmark. Benchmark is just dropping these benchmark posts in there, say, “Okay, here’s my first point.” When you’re finished talking about that, say “Okay, we’re now going to stop talking about that, and now we’re going to transition to the second thing I’d like to talk to you about today.” When you finish that, say, “Okay, enough about that. Now, I’d like to talk to you about the third and final thing I want to show you today.” When you’re benchmarking like that you’re letting the audience know where they are in the presentation. You have two choices. The audience has to learn how to remember this information. They’re going to create a structure in their mind to store this information. Think of it like a filing cabinet and you have two choices. You can make the audience design the system on their own. They have to label the drawers and all the folders and they will do that. Every human can do that. But while I’m doing it, it’s taking up processing power and I’m not hearing the speaker, I’m not listening as closely. The other option and the one that I think is the smart option is that you can create the storage structure for them. You can say, “Let’s label three drawers–my first point, my second point, my third point. Now, open the first drawer. I’m going to give you information to put in the first filing cabinet drawer.” And when you finish that point 10 minutes later say, “Now we’re going to close that drawer and open the second drawer,” and everybody knows where to put the information. If you don’t do this, people will design the system on their own and that works a lot of times. But they also make mistakes. They’ll put a piece of information in a place where it’s actually not supposed to be. A few minutes later they realize, “Oh, he wasn’t really talking about that, he was talking about something else.” They have to pull it out that folder, close that drawer, open another drawer, put it in a different folder, and the whole time that they’re doing that, they’re not listening to anything that you’re saying. You lose an awful lot of audience engagement and you really hurt the audience’s ability to remember what you’re talking about and engage with you further if you don’t give them the storage structure, the organizational structure ahead of time and then benchmark with them as you go through your presentation.

I wonder how many of our listeners were kind of losing track of what you were saying while they were trying to think of, “What was the file structure of what we’ve covered so far in these last 20 so minutes of this podcast?” I know I was. I was going off somewhere trying to think like, “What’s the structure of this? Did we have three main points so far? Was it four?” I love something that I’ve learned very early on in my career even before I was out in the real world when I was at the university, studying for PhD, my adviser, Dr. Niebert would tell me, “You’ve got to tell them what you’re got to tell them, then you tell them, and then you tell them what you told them.” That stuck with me for decades. I always made use of that. That was very valuable advice. What you’re describing is that on steroids. It’s really mapping out structures and giving those benchmarks or milestones, taking a lot of the effort out of the hands of the audience.

Some people laugh at that and say, “It’s like I’m back in my high school English class. That’s how my teacher used to grade us.” The reason you were taught that in your speech class or by your professor is because it works. You might say, “Well, that makes it kind of a boring presentation.” Sometimes you can go out there and not do that and you will get a standing ovation, but does the audience engage with you after the fact? If you want the audience to remember what you taught them, if you believe that your content changes lives, improves businesses, helps others, then you want them to remember what you’re talking to them about and this is one of the key aspects to doing that. There’s one other thing that you can do early in your presentation, called the linear path to learning, which will really help the audience feel that you’re engaging right on their level. A linear path to learning is to divide your audience into three categories and every audience has a spectrum, a spectrum of past knowledge, a spectrum of past experiences. I want you to divide your audience up into three different groups, least experienced, middle experienced, and most experienced, and then make a statement that sounds like this—I’ll give you mine when I’m speaking on stage—“Whether you’ve never spoken on stage before, whether you’ve given a few presentations but they haven’t been too great, or whether you give keynote presentations all over the country, this presentation is going to help you get to the next level and give you concrete steps you can take to improve.” What I did there was to break my audience up into three groups, least experienced, middle, and most experienced. Then I said, “This presentation is for you.” It’s actually the role of the speaker to help the audience see that they fit in this presentation–that this presentation is for them. This is one strategy that actually helps them do that. You coming right out and saying, “Whether you’re a beginner, whether you’re in the middle, or whether you’re on the top of this game, maybe know more about this topic than I do, this presentation will still be for you.” When you don’t do that, people often have trouble seeing themselves in your presentation. You’ll have people walk out and they’ll say, “Well, it was good but I think it was mostly for beginners. Not really for me.” Or, “It was good but I think it was mostly for people who have more experience than I do. I’m just getting started in this.” I was helping somebody with their presentation, which was actually on how to sell in webinars. I was watching them live; I was seeing them in the audience, in the end they pitched, I think, a $5000 program at how to sell better on webinars. I turned to the person on my right and said, “Are you going to buy this?” and they said, “No. I haven’t actually done any webinars yet. I’m just getting started.” I turned to the person on my left and said, “Are you going to buy this?” and they said, “No, I do webinars every week. I kind of know some of this stuff already.” I’m thinking what the speaker was missing—they didn’t sell a lot, they didn’t convert very well at all—what this speaker missing is actually this linear path to learning. If they would have said, “Whether you’ve never done a webinar before, whether you’ve done a few webinars and you want to get better at them, or whether you do one webinar every week and you just want to improve your conversion rate by 5%, my $5000 online course is perfect for you and we’ll help you get to the next level.” That linear path to learning would have had every single person in that room as an eligible buyer because they would have connected themselves right to it. At the beginning of your presentation, I like a linear path to learning that you can say about your presentation. At the end of a presentation, I like a linear path to learning about your offer. Either one will do. I usually don’t do both. I do one or the other. Here’s what you need to know. If the audience feels like your presentation was perfect for them, they’ll feel like your products and services are perfect for them. But if the audience feels like your presentation missed the mark, it was too advanced or too elementary, they’ll feel like your products and services are the same thing. They’ll feel like those aren’t perfect for them either. It’s really important whether you’re presenting on a webinar, a podcast, or on stage, that you make sure the audience knows that this presentation today is for you. Sometimes coming right out and saying it was a linear path to learning is the best way to do that.

This is such practical, concrete advice that you can start implementing immediately, like in your next conversation, not just your next speech. Break your audience up into threes or two, do the roadmapping at the beginning and say, recognize it “In these next 60 minutes we’re going to be talking on this podcast, I’m going to dah, dah, dah.” It’s such a little nuance, I can see the value of it and it takes what, 10, 15 seconds to work that into the presentation, it just requires some forethought.

Most of the changes that we make with the speakers we work with is in not lengthening their presentations. Most of what we do is shortened presentation. Most of the work I do when I’m working with top speakers is cutting things from their presentations because every presentation has things that are distracting from the path you’re trying to take a customer down or the path you’re trying to take the audience down. We include things that get them thinking about other things. That’s not your goal. You have a ton of funny stories and anecdotes that you can tell. We always put every one of them through a litmus test. Is this walking the audience down the path that we want them to walk down? It’s funny you mentioned that we’re delivering concrete steps here today because that’s really in the content portion of your presentation. One thing that I always check in every presentation that I work with is, are you delivering two things? One is short-term concrete stuff and one is long-term concrete stuff. Every presentation should be a mix of short-term and long-term solutions. Short-term are what I call quick hitters, some people call them quick whims. What those are, are things you can do right away. I like to think of them within 24 hours, here’s the change that you could make. Still today, here’s the change that you could make. Those are quick whims. Every presentation should have them. But you also should offer some long-term solutions, some habits you should take, some patterns that you should have in your life, and some systems that you should put into place. Included in every presentation, if you have both of these, the audience is going to walk out of there saying, “Wow, I got stuff I could actually use.” If you only have the short-term stuff, if you only have the quick hitters, people are going to think it’s a little bit elementary. They are going to enjoy the presentation but they’re kind of going to feel like that’s all you know and they have it all already. One of the questions you asked was, how do you stop from giving away all your good stuff but have the audience to engage with you further? The answer is to have a mix of short-term and long-term solutions. If you only give short-term solutions, the audience will feel like, “Well, there’s no need to engage any further because I got all of the stuff because they were all quick little things that I can do. I wrote them all down, and I can go do them.” But when you add the long-term solutions in, that over time here’s how you should think about journaling your stories so you always have stories to add to your presentations. I work with financial advisers. There’s quick hitters, quick wins like–here’s something you can check on your next paystub. Here’s something you can check when you watch CNN at night to see if this happened because that means this is happening. Those are quick wins. But they also need to give long-term solutions of systematically here’s a change that you can make. Over the next five years, start shifting this. When you give long-term solutions like that, people start to realize that, “Holy cow. You know more about this than I could ever understand and I need to engage with you further over a period of time to actually master all of this and to have you help me do this.” I can give you two quick things to change in your presentation tomorrow and it will make your presentation better, but I also want to give you some long-term solutions of things we’re going to watch the audience responds to and tinker with, watch the audience respond again and then change again. We’re also going to give you some closing ideas that, when you get to the end of your presentation, you should do and we’re going to work on those and find out which ones are most effective. Those are long-term solutions, not something you’re going to implement tomorrow but things that you can work out over the next year to improve any presentation. When I add that second part, those long-term solutions, you start to realize, “Well, wait a minute. I’m not getting everything he knows. I’m getting an outline of everything that he knows, but I really need to engage with him further to tap into that full vast wealth of knowledge that he has.” That’s why people want to engage with your further. I do think you should give your audience your best stuff, your very best quick hitters, your very best strategies. I’m a believer that if you give the audience your best stuff, they’ll pay you to have you say it again in a one-on-one setting, they’ll pay you to help them with it or pay you if not. I own all The Police albums and I’ve seen The Police with Sting in concert probably 10 times. Every time I go to see them, I want them to sing the same songs over again. I’m sure Sting’s sitting on there and like, “Well, last time you saw me I gave you all my best songs. You all probably never want to pay to see me again,” and actually just the opposite is true. Every time I go see him he plays all of his best songs that makes me want to go and pay to see him again. The one time that he didn’t sing Roxanne, I was so mad I promised I’d never go see him again, but I did. You should give your best stuff away but the key to getting people to engage with you even though you gave them your best stuff is include not just short-term solutions, but long-term solutions. Systems, patterns, and habits that people need to engage in, and then they’re going to realize, “Wow! I should engage with you over time or I should buy a done-for-me solution, or you know more about this than I ever will. I’m just going to have you do it for me.” It’s the long-term solutions that I actually do that, but if you only give long-term solutions, you might be thinking, “Well, I’ll just skip right through the long-term solutions. Then they’ll know they have to buy from me.” If that happens, and we see it all the time, the audience will walk out saying, “Well, I didn’t really get stuff that I could use.” That’s like, “What? I gave you stuff that you could do over the next three years to improve.” And then like, “Yeah, but I didn’t really get anything I could use now. I wanted things that I can do now.” That’s why every presentation has to be a mix, and actually in each section of your presentation, when people come to our two-day story execution workshop in Milwaukee, in two days it’s only six people around the table and we write your entire presentation. You walk out with your entire presentation, start to finish, all finished for you. We actually have a checklist where in each section, we go through and identify short-term solutions and long-term solutions to make sure that we’re not weighted too much towards long-term solutions or the presentation isn’t just filled with short-term solutions. It has to be a mix and that is what gets the audience to engage with you afterwards even though you’re giving them all of your best stuff.

Every presentation has things that are distracting from the path you’re trying to take a customer down or the path you’re trying to take the audience down. Share on XYou alluded to very briefly a long-term solution of teaching your clients how to journal their stories as they are dreaming them up or as they’re remembering them. There’s a capture system and they can integrate some of their best stuff that hasn’t been incorporated into their sales presentations or into their keynote speech as yet. Can you give us more color around that one?

We talked about episodic storytelling. We also want vivid examples in the middle of your content. There’s places where we want stories in your presentation at the very beginning, at the very end, and sometimes to flush out some of your examples to just bring them to life because in the middle of our presentation we don’t just want information, information, information that gets boring to listen to. Some speakers are natural storytellers and some salespeople are natural storytellers. There’s other people who really struggle to find the right stories and I’m always amazed when people hear me speak they’re just like, “Well you have some many stories. I don’t have stories like that.” I think one mistake that a lot of people make, and I know they make this because I actually judge speak-offs around the country. Different conferences will have speaking competitions and I’ll sit on the panel of the judges. One of this things that I see speakers doing wrong is that they think their story has to be absolutely extraordinary, like if I didn’t climb Everest or if I didn’t get abducted and held hostage for 20 days, I don’t have a story that the audience wants to listen to. One of the things I know is that the more ordinary your story is, the more of the audience it will reach. When you tell me that you climbed Everest by yourself using only one arm, that’s cool but there’s only one other person in the audience who can ever do that or even think about doing that. Where when you can tell me that one day the alarm went off and you thought about hitting snooze but you didn’t, you got up and started your day, and had a routine in the morning that helped you get started with a positive attitude, that’s a story that every single person in your audience can relate to wanting to hit the snooze button. That’s a better story than climbing Everest. That’s a better story than being abducted and held hostage because more of the audience can relate to it. When people are thinking about their stories, the first thing you want to do is don’t think a one-in-a-million story because if you have a one-in-a-million story relate to one in roughly one million people in your audience. Instead, think of a story that everybody experiences every single day. “I came to a four-way stop and two of us got there at the exact same time, and here’s what happened.” Everybody’s with that story because you’re thinking, “Well, what happened? Did you wave him through? Did you both try to go at the same time?” Everybody’s with me on that story. I really want to encourage you that the more ordinary your stories are, the more they will relate to your audience, the more your audience can relate to them. One of things that we have people do is journal their stories. I keep three things–three columns in my journal. One is the story itself, what the story is, what happened. “I went to the grocery store and I saw somebody who can’t reach the top shelf and here’s what I did and here’s how they responded.” Second column is what lesson it teaches. Some stories have multiple lessons that could teach helping others, that could teach take action, that could teach awkward moments, something like that. Then third column is how long the story takes to tell. When I’m putting together a presentation and I’m thinking, “Okay this is a 15-minute interview that I’m doing here. I need some short stories and here are the things I want to teach. I’m not just thinking in my head what stories should I tell. I can actually go to my story journal and say, “Okay, I need a two-minute story, nothing more than two minutes because it’s only a 15-minute interview, and here are the three things I want to teach.” I can sort mine in Excel database, of all things. I can sort it by length of story, I can sort it by what it teaches, or I can look at the stories themselves. Many people have things happen to them that would make great stories and teach great lessons to their audience, but they’ve never taken the time to actually write them down. When the pressure’s on like, “Hey you need to give a presentation tomorrow,” and your brain’s a little but in panic mode as many people get as a presentation comes closer, it’s so much harder to think back and find them. But when they’re happening in an ordinary day, it’s pretty easy to write them down, jot them down, and the lesson you can teach from it. Then you can pull them out when you need them, and you’ll always be able to remember them.

That’s great advice. It kind of reminds me of Matt Church has this process he calls Pink Sheets when you get some of your IP out of your head by creating the structure where you got the concept and the explanation of that concept, you got a metaphor for that concept and you can have a catalog of your IP as this collection of pink sheets. Then you got a presentation, you start pulling out relevant pink sheets and that becomes your slide deck. You got stories, case studies, processes, statistics, and all that as part of these pink sheets. That’s a really cool process. I’ve been using it myself. This sounds a little bit similar to that but different. I love it. I think it’s a great strategy for folks–everybody really should join.

I think you can use both strategies. I don’t call them pink sheets, I call them index cards where I have the different things I can juggle around in any presentation, every little anecdote and teaching point is on an index card. Sometimes when I put a presentation together, I can lay out the order I’m going to do them in but then juggle things between sections to even up the time, the sections, things like that, and pick different spots. I don’t think the two techniques are mutually exclusive. I think story journaling is something that everybody is going to speak or sell or be interviewed should do, so that they have these stories. I think the pink sheet is great when you get to the organizational part of it. I think that’s those are two strategies.

I agree with you on that, for sure. A lot of presentations, webinars, and selling from stage sort of presentations are teach, teach, teach and then sell, sell, sell. Then there’s this awkward transition in between the two. Then you feel like, “Now’s the time to get a drink or go to the restroom because now we’re in sales mode.” What do you tell people who are taking that approach?

I’m glad you ask that because the most common comment I get from speakers I work with is, “I don’t like to sell,” and everybody listening has probably in the room where there’s been that awkward pivot, where the speaker goes from “Okay, enough about me helping you. Let’s talk about how you can help me.” Two things I know–I know the audience is uncomfortable, but I know, because I work with them every day. The speaker is uncomfortable, too. I see even the most confident speakers at this point start to back up–which you should never do during your offer–start to close up, instead of having arms and hands open like you should with nothing between you and the audience, they clasp their hands in front of them, closing off themselves from the audience, a position you should never be when you’re on stage. Even the most confident of speakers will start to look down, back up, and close themselves off from the audience. I know the audience is uncomfortable but I know the speaker is, too. The solution is instead of saving all of your offers before the end of the presentation, the solution is to embed your offer into the content of your presentation. The reason you want to do this is because the human mind is really good at one thing. The human mind is really good at categorizing. We listen to information and we drop it into categories. “Hey, that’s a story. I don’t have to listen to all the details.” “Hey this is information. I should listen to the details and take notes. One thing that we’re really good at categorizing is, “Hey, this is sales talk.” When we listen to information, we listen carefully, we believe the speaker, and we often take notes. When we listen to sales, we put up our own objections, we listen skeptically, and we often assume that the person is not telling the truth. When you embed the portions of your offer into the content portion of your presentation, you get people listen to your offer with an information mind, which is why they’re going to gobble this information up. Oftentimes, if you do this correctly, they’ll take notes on your offer during the presentation. How does this sound? In your presentation, you already give examples. Halfway through your presentation you probably stop and say, “Okay, well Bob was somebody who did this and he went from 5% up to 35%. All you have to change is you’re going to give that same example but you’re going to take five seconds in the beginning and tell us how you engaged with Bob. Here’s the key. Bob’s going to engage with you the exact same way that you are going to offer at the end. At the end if you’re offering an online course, “Bob is somebody who took our online course and we moved him from 5% to 35%.” If you’re offering one-on-one coaching, “Bob is somebody who’s in our one-on-one coaching program and we moved him from 5% to 39%.” If you’re offering a big event in Las Vegas, “Bob came to our big event in Las Vegas last year, and then we moved him from 5% to 35%.” Or if you offer services, “Bob is one of the persons who utilized the service and we moved him from 5% to 35%.” Now, the ratio is really important. The ratio is five seconds of how I know Bob, and five minutes of content. Usually, when a presentation feels wrong, when a presentation feels like it was sales-y, it’s because the speaker got the ratio wrong. They have a 50-50 ratio or even a 60-40 ratio between content and selling. What we want is five seconds of how I know Bob, “Bob was somebody who signed up for our two-day story execution workshop in Milwaukee.” Then five minutes of content, “Here’s something I taught Bob. I taught Bob a linear path of learning.” Then content, content, content, content. At the end of that, people are going to be like, “Wow. That’s great information, and for some reason, I want to come to Milwaukee for your two-day workshop or I want to sign up for your online course.” They won’t even know why they want it. They’ll just know that they want it and that you gave them great information. We recommend you do this two or three times and when you come to Milwaukee for our two-day story execution workshop. We actually help you figure out where are the two places where you should put this in your presentation–usually once in your first section. Some people are thinking about the fact that, “Hey people. Dude take your outline course or you have any even coming?” and then one later on. Each time you bring it up, you tell one different detail. The first time you tell about your online course, you might just be like, “we have an online course.” Mary Lou was somebody who took our online course and here’s one question that she had and how we answered it. “Content, content, content, content.” Ten minutes later you might say that, Lenny was one of the people, he took our outline course. The online course only takes six weeks, there’s a video every week in a live coaching call. Last week in our coaching call, here’s one of the questions that Lenny asked–”Content, content, content, content.” If you drop one detail each time, when you get to the end you know it’s a online course, it lasts six weeks, it has this many lessons, and there’s live coaching involved with it as well. When you do get to the offer portion of the end of your presentation, your call-to-action, if that’s what you would call it, it’s much shorter because you don’t have to go through and list all the details. They already know all of the details. Really, your call-to-action at the end then–is just going to be logistics, like, “I know you already want this. Here’s what you need to do. Here’s where you need to go.” It’s really more of a logistic call-to-action at the end than it is a selling call-to-action because they already want it. You’ve attached it to the information. The key to this whole thing is that the human mind that is listening, is listening with a totally different orientation. It’s listening like information because it’s in the content portion of your presentation, and it’s five seconds not 15 minutes of selling. It’s five seconds of “Here I know somebody” and they attach it to your content. The beauty is that they will always attach that offer, whether it’s a service offer, an event offer, a coaching offer, webinar, an online course offer, they will always attach it to your content. If you ask why are you going for that or why did you sign up for that, they’re like, “It teaches us great stuff.” “How do you know it teaches great stuff?” They just know because it was attached to it in the content portion of your presentation. It changes everything. It changes people who are uncomfortable selling, be it a very natural process, but also changes the audience and how they receive the offer. They receive it believing, they receive it with details, they might even take notes on it if you do it correctly.

That’s awesome. What’s the name for this again? I think I heard of this concept as seeding?

Some people have called it seeding, I call it embedding. I want to embed a couple of things in the content portion of your presentation not just examples of your next level of engagement. By the way, we shouldn’t try to embed three different offers. Our decision before we go and speak is, for this audience and their level of qualification, what they’ve shown they’re willing to invest, how much experience they have, and how far they came to be here, for this audience, what is the next right level of engagement? If it’s an unqualified audience, that might be just to lead them into a free webinar that you can spend more time selling. If it’s an unqualified audience, it might a low-priced offer, or if it’s a highly qualified audience that has already shown their willingness to invest in solutions, it might be a higher-priced offer. But you can only lead them down one path. You can’t embed a $500 offer at the beginning and embed a $15,000 offer at the end. They’ll freeze and they’ll have to go wait and think about it for two years before they decide which of those two is right for them. You have to choose for this audience, what path do I want to lead them down. The other thing that we want you to embed in the content portion of your presentation is your testimonials. We’ve all probably been in presentations where near the end of the presentation the speaker shows three consecutive slides with pictures of people you may or may not know and quotes that I wrote right before the presentation for them. Everybody said, “Okay, these aren’t real quotes.” We know how this works. I wrote a quote, I emailed it to you and said, “Hey, would it be okay if I say this about you?” and they mail me back and say, “That would be okay.” They’re three in a row and it’s just terrible. Instead, what you should do in the content portion of your presentation, you should embed examples of how you helped specific people that actually do the testimonial right in the middle of it. Embedding is actually the technique that we taught Nicholas Kusmich. Nicholas Kusmich, if your audience doesn’t know him is a Facebook Ads guy. He was giving a presentation with a $5000–$6000 online course on the backend. When I started with him, he was closing in 5%–6% in the room. All we had him change, the only thing we had him change was to embed all this great content, all this great examples—Nicholas is great on stage, don’t need to improve his presentation style, that’s for sure—all we did was have him embed his examples and say, “Okay, this example is one of the things that we teach in our online course,” and he dropped one detail about it. Then later in the presentation, when he was talking about picking the right image or trimming your audience, or something like that, he said, “No, this is something that we teach in our online course.” Two times in his presentation, he embedded the same examples he was giving and attached them to his online course, and at the end of that presentation he closed at 39% on a $6000 offer in the room. That’s the sort of change that embedding can make. Now, did you see what I did there? I could have, at the end of my presentation, put up a slide with Nick’s picture on it and said, “This is what Nicholas Kusmich said about me, that Quinn got my offer to go from 5% to 39% by making very small changes,” and everybody would have looked at that and said, “Yeah, I bet Nick said that. I bet he just said those words in italics just like you have from up there.” Instead, what I did was I attached Nicholas Kusmich’s example to my content. I gave it to you while I was teaching you embedding. Nobody questions that that happened, because it was attached to my content. You know it happened. You actually know how it happened. I attached it right to the content that made it happen. Now all you want to do is work on your embedding. You want to engage with me further. The technique which I just did to you is actually to not have your testimonials at the end but actually to attach them to your content that caused the testimonial to happen. Take your three testimonial slides and instead of doing them at the end, think about, “Well, what is it that helped this client so much that they gave this testimonial?” and find that spot in your presentation and put it there as a story about the content, not just a testimonial slide at the end of your presentation. Those are the sorts of things that we systematically embed. We embed them in our webinars and it changes the conversion rate. We embed them in our keynotes and people flock up to the stage afterwards. We even embed them in our one-on-one phone conversations with prospective clients, or over the table at a coffee house or over lunch, so we don’t have to do an awkward social proof of pulling out our iPads and flipping through some testimonials, or pulling out a three-ring binder with testimonials in them. Instead, it’s built right into our content story, it’s so much natural, it doesn’t feel like selling, and honestly the audience doesn’t even know what happened to them.

That is so good. Nicholas is actually a friend of mine. I had him on my Marketing Speak podcast twice.

I hope that he’s getting better at his embedding.

I’m sure he is. His two-day storytelling workshop in Milwaukee as well.

That would be great.

To wrap up here, let’s say that at the end you make an offer, and whether it’s a $6000 course or in-person training like Nicholas has, or it’s an online training, maybe it’s a six-module online course and maybe it’s $997, or you want them on a call, let’s say for SEO consulting services, ISO, SEO–I want to get people on a call to whether they’d be a good fit and vice-versa, that might be a call or strategy call sort of session as a call-to-action. Do you have a particular kind of go-to strategy for this where you’re always asking people to do a call as the next step because that’s where you’re going to close the big dollars or does it depend on the situation?

It depends on the situation and the qualifications of the audience. This is something we spend a lot of time in-house sitting around the table discussing. We’re going to speak at this big event in Tucson next month. How qualified are they? What have they invested previously? Is it a local audience or an audience that flew there because if they flew there, they are already willing to invest? Are they already in someone’s coaching program? They’re $6000 in already. They’re willing to invest or is it a free audience? Is it a local audience which really hasn’t shown much commitment? An unqualified audience, I think you want to leave them into their free call, free webinar, free additional training, that will give you more time to nurture them and separate them honestly into which ones want to invest. Some people did this through the application that you have to apply for a free call and I’ll ask you a couple of–like Russ Rufino’s qualification questions and how much are you willing to invest in yourself. There’s some questions that you can ask in a free call application that will help you sort them into which ones you want to do and which ones you want somebody else to do. I think if it’s an unqualified audience to lead them into a low-cost or free offer and if it’s a qualified audience, you can take them right to a big offer. The transition from content to offer is always difficult for people. We love a grassroots transition which sounds like this. One of the most common questions I get is, “Pat, can I work with you further?” I did two techniques there. I didn’t want to say, “Okay, now enough about content I have to tell you about my offer,” because that’s awkward. I did a grassroots. One question that a lot of people ask me is, “Can we work with you further?” That’s one technique that I showed you there. The other technique that I showed you there is I referred to myself by first name in conversation. A couple of times during any presentation, you should refer to yourself by first name in conversation. I was at the grocery store the other day and somebody come up to me who I knew and said, “Pat, you’re still working …” It doesn’t really matter where it is but you have to have it happen. The reason you have to have it happen is because you want people thinking about engaging with you further. If you do this, they will all automatically start picturing themselves like, “Hey, if I were going to talk to you after you go off stage, if we’re going to email you afterwards, I’d probably start with, “Hey Pat.” That’s how it would look. Nobody really does this better than Joel Osteen. Joel Osteen is a pastor at one of the largest churches in the country, like 40,000 people go the services every weekend. He’s usually up on stage in front of 10,000 people. But two times during every 25-minute message that he gives, he talks about people coming up to him and saying, “Well Joel, what should I do about this?” or I was in the back of church last week and somebody walked up to me and said, “Joel, can you answer this question for me?” I’ve watched people come up to him afterwards, and when they shake hands with him and come up to him, they’re a little bit starstruck as they see him on TV every week, but they come up to him and they don’t say, “Hey Pastor Osteen,” they don’t come up to him and say, “Mr. Osteen.” They come up to him, they’re like, “Joel!” like they’re best buddies with him from childhood. I’m like, “Why does that happen?” The reason it happens is because he teaches it to happen. He makes it happen. He makes them think about having individual conversations with them. If you say near the end of your content, one of the most common questions I get—that’s your grassroots entry in there—is “Hey Pat, can people work with you further?” The answer to that question is, “Yes, people come to Milwaukee for a two-day story execution workshop.” What I did there was a grassroots entry into it. Then we want you to have two different closes. One is a tactical close. A tactical close is just logistically, “How do you do it? How do you sign up for it? Here’s the website that you go to. If you have questions, you can email me at this address.” Those are the tactical closes. Then the final thing you want to do, you don’t want to finish on your tactical close because at the very end of your presentation is actually not where you have the highest audience attention. At the very end of your presentation, the audience is actually thinking a lot of things. That bandwidth that we talked about as being used up by how long the bathroom line is going to be, or if you’re on a webinar, I got to put my kids to bed now, or I’m going to check my email now. It’s just used up by a lot of things. But you do want to do a second close. At the very end of your presentation should be spent on an emotional close. You’ve two different types of people in your audience. You have tactical people who want to know all the details. “How many lessons are they? Are they released one a week? Can I get them all at the beginning? How much does it cost? Do you take American Express or can i3 pay?” You have those people in your audience but you also have the emotional buyer in your audience who really doesn’t care about that. They’ll buy it and then ask you afterwards, “How many lessons are there?” They’ll buy it and then ask you afterwards, “Are they audio lessons or video lessons?” They didn’t even check. You put them in an emotional state and that’s where they buy them. I know some people are really good tactical closers. They know how to stack an offer and tell all the details. They do it really well, but they don’t close the emotional buyers. I know other people who are really good at the emotional close. They can leave the audience all lathered up, but they don’t close the tactical people because they skipped all that. The key, if you want to close your entire audience and convert them, whether it’s a call or a free offer or a really expensive offer, they key is to close them both. That requires a tactical close followed by an emotional close. The emotional close is usually a story that we close with that leaves the audience in the state that you want them to be in. Oftentimes in a live event, that state is I want you to take action now before you leave here today. I want you to pull out your credit card now or fill out the card now or fill out the application and give it to me before you leave here today. Don’t go home and think about it. Do it now. The story you want to tell there is an ordinary story about how taking action makes a difference. When I get to that point, I might want to tell a story about this, “We’re down in Florida over spring break.” or my daughter was, “Can we get up tomorrow morning or early and watch the sunrise? I bet it would be really cool.” I said, “Yeah, we can do that.” I set my alarm for [5:15]. When the alarm went off at [5:15], there was nothing I wanted to do more than to stay in bed because it’s warm in bed and that was going to be cool outside, I was tired from the night before, but I did. I shut off the alarm and I got up. Was I ever glad that I did because our family, my two daughters, my wife and I, we saw one of the most amazing sunrises we’ve ever seen, and it’s just this moment for our family where we really got to take stock in what’s important in our lives and how we felt about each other, and it’s a moment I don’t think that any of us are going to forget for a really long time. Then stop, turn to the audience, and now teach–I think there’s times in all of our lives where we have a choice, to take action immediately, or to put it off. What I learned is that the people who take action immediately are the ones who get the benefits of those amazing sunrises.” What I did there was told a story, an ordinary story about wanting to hit the snooze button. This is not a story about kayaking down the Amazon River and man wrestling an alligator that only one person in the audience would have ever done. This is an ordinary story that everybody has experienced wanting to stay under the covers and hit the snooze button. But I taught the point that I want them to learn, which is taking action makes the difference. The person who has those amazing moments is the one who took action. That leaves the audience in an emotional state that you want them in to take action immediately. Different offers need different emotions. Sometimes, people have been doing it the same way, years, and years, and years, and years, and they never change. You want to tell that type of story. If you’re trying to get someone to switch from the provider that they’ve been using for years to you, you have to tell that type of story. Sometimes, people try to do it on their own and they need a mentor, and you want to be their mentor or their coach. You want to tell a different story, a story about a time that you struggled and struggled and struggled, then you reached out and finally asked for help, and that made all the difference. Think about what is the emotional state that I want the audience in so that they make this decision to work with me. That’s different based on the type of offer. A coaching offer is different from a switch-your-normal-provider-to-a-new-upstart-offer which is different from take-action-before-you-leave-the-room-here offer. But tell a story that leaves them in that emotional state. Then you’ve got the tactical people who tactically want it, and the emotional people who emotionally want it, and you just better have a lot of people there ready to process credit cards when that’s done correctly because you’re going to close every single person in the room when that’s done right.

Wow. I’m ready to sign up. I’m very impressed. I don’t know if I’m a tactical buyer or an emotional buyer but you had me with all the tactics and strategies and then you had me again with the emotional close. That’s amazing. Thank you so much, Pat. If somebody wanted to work with you do the two-day story execution workshop or work with you on more ongoing coaching basis, whatever, how do they reach out to you?

The website is advanceyourreach.com. We can put a real specific link on this so you can get right to the story execution workshop page as well, but the basic website is advanceyourreach.com. If you have additional questions about it you can email me anytime at [email protected]. I’ll be happy to help you with anything that you’re struggling with in your presentation.

Thank you so much, Pat, and thank you, listeners. Now, it’s time to take action, whether that’s signing up for his workshop, or it’s to go download the checklist of this episode. This is Stephan Spencer, your host. We’ll catch you on the next episode.

Important Links

Connect with Pat Quinn

Apps/Tools

People

Previous Marketing Speak Episodes

Previous Get Yourself Optimized Episode

Your Checklist of Actions to Take

- Know who my target audience is and what their problems are. This will help me approach them with solutions.

- Speak in my audience’s language to make them understand my message. Building a good rapport will help me get important points across.

- Take note of the mantra “sell them what they want but give them what they need.” Make my sales pitch provide high-value assets to my audience.

- Be ordinary, be extraordinary and show my why. These are the 3 things I should cover in the first 5 minutes of my presentation.

- Sharpen my storytelling skills but don’t overdo it. People respond better to stories that they can relate to but they will know if you’re bluffing.

- Film the audience during my speech to watch their reactions. Evaluate at which point they respond the most and the least to my message.

- Create a speech roadmap to let my audience know what’s in store for them. Make them aware of the bigger picture to help them stay engaged.

- Summarize key points at the end of my speech so that my audience will have key takeaways.

- Give the audience my best material. If I give them high-value strategies for free, chances are they are going to want to pay to get more from me.

- Make it a goal to improve people’s lives through speaking. Focus more on helping and not selling.

About the Host

STEPHAN SPENCER

Since coming into his own power and having a life-changing spiritual awakening, Stephan is on a mission. He is devoted to curiosity, reason, wonder, and most importantly, a connection with God and the unseen world. He has one agenda: revealing light in everything he does. A self-proclaimed geek who went on to pioneer the world of SEO and make a name for himself in the top echelons of marketing circles, Stephan’s journey has taken him from one of career ambition to soul searching and spiritual awakening.

Stephan has created and sold businesses, gone on spiritual quests, and explored the world with Tony Robbins as a part of Tony’s “Platinum Partnership.” He went through a radical personal transformation – from an introverted outlier to a leader in business and personal development.

About the Guest

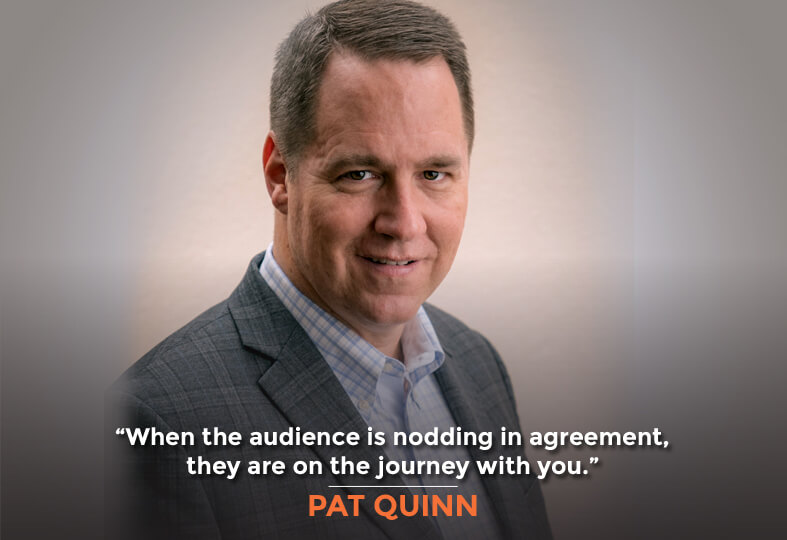

PAT QUINN

Pat Quinn is a presentation coach for some of the best speakers in the world. As a former professional magician and teacher, he understands how to control the audience’s attention and how to help them learn and remember your content. www.AmazingPresenters.com.

Leave a Reply