Want to stop procrastinating, achieve your objectives, and hit your targets? The secret is to learn how to become “indistractable.”

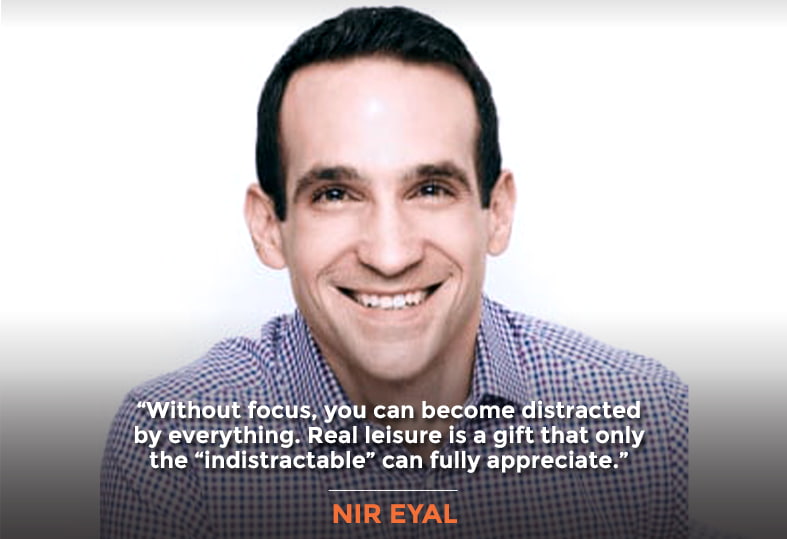

Nir Eyal, bestselling author of books Hooked and Indistractable, is my guest on today’s show, and he’s here to help. Nir has taught as a lecturer at Stanford Graduate School of Business and founded several technology companies. His work focuses on how to build good habits in life and business while breaking bad ones.

In this episode, we debunk the myth that technology steals our focus—it’s how we use the tool that matters. We explore how reflective work stacks up against reactive work. Reactive work is time spent attending meetings, taking calls, and responding to emails. That’s where most of our day goes. But reflective work is where the real payoff is, because it’s where problem-solving, future planning, and creative work get done. You’ll also learn why consistency trumps intensity for forming lasting habits. Nir also explains his process for writing bestsellers by following curiosity, and how manifesting passion projects requires finishing the last mile. He shares thoughts on how AI and augmented intelligence will transform marketing. He provides perspective on overcoming our negativity bias and maintaining an optimistic mindset during technological disruption. For anyone eager to achieve traction in achieving their goals, this is a must-listen episode.

So, without any further ado, on with the show!

In This Episode

- [02:26] Nir Eyal discusses building good habits and breaking bad ones through product design.

- [04:09] Stephan talks about the common attributes of habit-forming applications like Instagram, such as user engagement and addiction, prompting Nir to argue that those applications are not inherently good or bad but rather how we use them.

- [06:39] Nir differentiates distraction and traction in our personal and professional lives, highlighting the most dangerous forms of distraction and turning value into time.

- [13:23] Stephan struggles with a long to-do list, prompting Nir to propose the timeboxing technique as a more effective alternative.

- [26:34] Nir shares how his connections emerged when he followed his curiosity and recalls how he ended up doing a quest for Mindvalley.

- [42:49] Nir explains the potential benefits of AI in healthcare.

- [47:18] Nir describes the impact of technology on society and individual well-being.

Nir, it’s so great to have you on the show.

Thanks so much. It’s great to be here.

Let’s talk about how you went from helping companies figure out how to create habit-forming addictions in users to helping users become non-manipulable in terms of their usage of such products.

Sure. Let me start with some definitions. Nothing I ever wrote was about how to build addictions, okay? Addiction is a persistent compulsive dependency on a behavior or a substance that harms the user. We would never want to build a product that is inherently and intentionally addictive. What we do want to build is a habit.

What is a habit? A habit is simply an impulse to do a behavior with little or no conscious thought. Unlike an addiction, which is never good, there’s no such thing as a good addiction by definition. We can help users build good habits. That’s what Hooked is all about. How do we get hooked on healthy habits?

If Hooked is about how we build good habits, Indistractable is about how we break bad habits.

For example, Kahoot uses the Hooked model to get kids hooked on education. We can use the Hooked model to get people hooked on exercise and well-being as Fitbod does, a case study in the book as well. There are all kinds of industries, from enterprise products to healthcare and Fintech to EdTech. All kinds of products have used my work to get people hooked for good.

The other side of the coin is that while we want to build good habits, we want to break bad habits, but these are two different products. Let me be very clear. I have never worked for video game companies. I don’t work with alcohol, tobacco, and online gambling companies because I don’t want to help these types of companies build unhealthy addictions. These are the kinds of products and services that I want people to stop using to put them in their proper place.

Indistractable is about, for all of us and for every type of product, not just social media, gambling, or whatever the case: How do we make sure that we do what we say we will do? If Hooked is about how we build good habits, Indistractable is about how we break bad habits.

Thanks for that clarification. If you looked at what Instagram is doing, any of these other very habit-forming or addictive apps that people get unhealthily attached to, what are some of the common attributes or components of software like Instagram?

I would argue that any form of media, whether it’s social media like Instagram, legacy media like the newspapers, or cable news, all of these forms of content, all of these business models depend upon user engagement. We tend to vilify the new products because we always morally panic about new technologies. But look, the New York Times, the paper of record, will never tell you’ve had enough.

We have people we call news junkies who are pathologically addicted to the news. We probably know some people in our lives who are way too up-to-date on everything. That’s too much. It’s not just about technology; it’s more about how these things fit into our lives. Is keeping up to date on the news a good idea? Of course, it is, but in moderation, like all things.

Social media as well, from a user perspective, can be great. I can’t tell you how many friends I keep in touch with because of these miraculous technologies that I use for free that help connect me to my readers, my loved ones, my friends and my family. These tools are not inherently good or bad, and it’s about how we use them.

I’m trying to shift the conversation away from waiting for the social media companies to do something about it because that will never happen. And waiting for the geniuses in Washington to do something about it. Good luck. Why hold your breath? If you hold your breath, you’re going to suffocate.

I want people to realize, “Yes, these products are designed to hook you.” I know, and I wrote the book Hooked. I know all their tricks. I will tell you, they’re good. They’re not that good. We like to think that these products are mind control.

There’s been a book written called Stolen Focus. That’s ridiculous. Our attention is not being stolen, and we’re giving it away. We, as consumers, need to be very aware of how we can get the best out of these products without letting them get the best of us.

Yeah, that’s great. I love what you explained in Indistractable that distraction is not the opposite of focus but the opposite of traction. That is such a powerful distinction. Can you elaborate a bit about that?

Sure thing, yes. It’s important to understand where these words come from. I realized that I didn’t understand what distraction meant in my own life, so I started from first principles. If you look at the origin of the word distraction, if you want to know what distraction is, ask yourself what is the opposite of distraction.

Most people will tell you the opposite of distraction is the focus. I don’t want to be distracted, and I want to be focused. But that’s not exactly right. The opposite of distraction is not focus. If you look at the origin of the word, the opposite of distraction is, of course, traction. We have traction and distraction. I didn’t realize that relationship until I saw them side by side. They are, in fact, opposites.

Traction is any action that pulls you toward what you said you would do, pulling you toward your values and becoming the person you want to become.

We know both words come from the Latin root trahere, which means to pull. They both end in the same six-letter word: A, C, T, I, O, N, which spells action, reminding us that distraction is not something that happens to us but rather an action we take. Traction, by definition, is any action that pulls you towards what you said you were going to do, pulling you towards your values and becoming the kind of person you want to become. Those are acts of traction.

The opposite of traction, distraction, is any action that pulls you away from what you plan to do, away from your values, away from becoming the kind of person you want to become. This is really important. This isn’t just semantics because any action done with intent, anything you plan to do in advance, is an act of traction. We need to stop moralizing and medicalizing these perfectly fine behaviors. If you want to go on social media, if you want to watch Netflix, if you want to play a video game, there’s nothing wrong with any of this stuff. Stop moralizing this.

I hear people saying that social media is so evil. And why is watching football on TV for three hours somehow better? There’s no difference. In fact, I would much rather have people interacting with others than sitting by themselves watching a game on the boob tube. Anything you plan to do in advance with intent is traction.

Conversely, anything that is not what you plan to do in advance is a distraction, even if that is a work-related task. What I found in my five years of research working on this book is that the most dangerous forms of distraction are not the ones that we typically expect. We think distraction comes from our phones and social media. It turns out the most pernicious form of distraction is the distraction we don’t even realize is happening.

For example, I used to sit down at my desk every morning. I would look at my to-do list. By the way, we can talk about why to-do lists are one of the worst things you can do for personal productivity if you don’t do it correctly. We can talk about that later.

I would look at my to-do list and say, “Okay, I’ve got that big important project I have to work on right now. Nothing’s going to get in my way. Here I go. I’m going to get started, and I’m going to focus with no distractions. Except, let me just check my email real quick. Let me just scroll through my Slack channels for a quick minute. Let me just get updated on the world news because that’s important. All this stuff is important for my business, and I have to do this every day. I have to do this for my professional well-being.”

What I didn’t realize is that just because it’s a work-related task doesn’t mean it’s not a distraction. That’s the most dangerous kind of distraction because those are the kinds of tasks that trick you into prioritizing the urgent and the easy work at the expense of the hard and important work you have to do to move your life and career forward.

Just because it’s a work-related task doesn’t mean it’s not a distraction. That’s the most terrible kind of distraction because you don’t even realize that you’re distracted. That’s a very important dichotomy between traction and distraction revealing to us.

This is the big takeaway. I want everyone to write down who is listening. I want you to remember that you cannot call something a distraction unless you know what it distracted you from. I’ll say that again: you cannot call something a distraction unless you know what it distracted you from. If you don’t know what you want to do with your time and attention, everything’s a distraction. You have no right to say you got distracted unless you knew in advance what you wanted to do with your time.

Any action done with intent and anything you plan to do in advance is an act of traction.

Just because you check email or Facebook a lot, you do too much. If you don’t know what the alternative is that you would have done with your time and attention, then you can’t say you got distracted. This is why it’s so critical, and one of the four steps to becoming “indistractable” is making time for traction by turning our values into time, and we can talk about exactly how to do that.

Yeah. I know this is a marketing show, but this is so important. We did an interview several years ago now on my other podcast, Get Yourself Optimized, episode 218, for all this great stuff about becoming “indistractable” because this is, I think, your superpower, the listeners’ superpower. If you can become “indistractable,” you can achieve your dreams. It’s not just, as Nir said, becoming more productive or more focused. It’s about getting what you want out of life because you have traction.

Let’s shift over to marketing. But first, I want to mention a couple things crucial to this conversation about being “indistractable.” I was reminded of something I learned from nonviolent communication, Marshall Rosenberg. When you were talking about traction, I remembered his teaching that said do not should all over yourself because we do that a lot.

When you were talking about moralizing, I was thinking about that statement: don’t shoot all over yourself because that’s the moralization. “I know I shouldn’t be watching this Netflix show. I know I shouldn’t watch yet another episode of it. I should go to bed.” Stop shoulding all over yourself, stop moralizing, and just get in touch with what you actually want, and then make your choices.

Very well said, right? There’s nothing wrong with watching Netflix. It’s about the right time and place to watch Netflix. In fact, I want you to schedule time for that stuff. When people say, “I’m on social media too much,” or “I find myself distracted at work because I’m thinking about this, that, or the other,” it turns out you can schedule that time and use it without guilt.

One of the things that I think very few people have actually experienced is what real leisure feels like. The problem is that unless you follow these techniques to become distractible, even when you have leisure time, even when you’re with your kids, you want to watch something on Netflix, or you just want to relax and do nothing, even when you do that, you’re still thinking about all the unfinished tasks. You’re still thinking about all the stuff you haven’t finished on your to-do list, so you don’t actually enjoy true leisure. Whereas an “indistractable” person has on their schedule, “Hey, this is time to be with my family,” or “This is time to go on social media,” and they can do so without guilt.

Yeah, so good. I also want to circle back to what you said about to-do lists. Can you elaborate a bit about how bad they are?

Sure.

Just to preface this, by the way, I have at least 6000. I haven’t actually counted them because my to-do list manager, which is called Things by Culture Code, doesn’t actually give me the entire number, just the number in the inbox. Anyway, there are probably around 6000 items on my to-do list. I know that’s insane.

Six thousand items on your to-do list?

Yeah. It’s draining my energy. It’s terrible. I know. I’m a packrat. I am a hoarder when it comes to my ideas, my next actions, someday maybe, and all that I’m speaking in GTD.

Okay. I love it.

I do understand productivity and how it works, time management, and so forth. But I’m not actually applying it. I’m using the to-do list as a place to park everything under the sun and not calling it. I know that’s bad.

You cannot call something a distraction unless you know what it distracted you from.

Amen. Here’s the thing: it’s not your fault. I think it’s a fatal flaw of this to-do-list method in that to-do-lists have no constraints. They have no constraints. As you said, you have 6000 items on your to-do list. You can add more, and more, and more, and more.

The problem with that, Stephan, is that when you, like many of us, like I used to be, live under this tyranny of to-do lists. We come home from work, and it’s been a busy day. We’ve worked our butts off, and yet here are all these things that we said we would do that we didn’t do. What does that do to one’s psyche?

If day after day, week after week, month after month, year after year, you are reinforcing that you made promises to yourself that you didn’t keep, loser. People start saying silly things like, “Well, I’m no good at time management.” No, it’s not that you’re not good at time management. It’s that this technique is no good. That’s one fatal flaw.

The second fatal flaw with to-do lists is that to-do lists have no feedback loop. People tend to fall into what’s called a planning fallacy. The planning fallacy says that, on average, and studies have confirmed this, a task will take you three times longer than you estimate. The problem is when we use a to-do list, and there’s no feedback loop to tell us how long things take, as opposed to a much better way, which is what I propose. I didn’t make up this technique.

This has been shown in thousands of peer-reviewed studies, and this is the most widely study time management technique, the most effective technique we know of, which is called timeboxing, which is essentially using what’s called setting an implementation intention, which is a fancy way of saying, planning out what you’re going to do and when you’re going to do it. When you set aside that time for what you want to spend time doing, that has been shown to be much more effective.

I take it to another level. You’ve probably heard of timeboxing before. Here’s what’s new. Here’s what my research reveals. What I want you to do is when you make that time box, when you set in your schedule, “I’m going to work on X, Y, Z,” or “I’m going to do whatever it is I’m going to do with my time and attention.” When I set that time, the goal is not to finish.

So many of us have been trained with the to-do list method to think we are good people who are productive when we check off cute little boxes. What that leads to, and we’ve all been there, is either working on the wrong tasks because the worst distraction is a perfectly done task that you didn’t need to do. What to-do lists incentivize is checking off cute little boxes.

I’ve actually known people who will finish a task, but they forgot to write on the to-do list, so they’ll write on their to-do list just so they can check it off. That’s how insane this methodology is.

The goal of my methodology is not to finish the task. The goal is to work on that task or do that thing that you wanted to do for as long as you said you would. If you said, “Hey, I want to do 30 minutes with this presentation,” or “I want to spend 30 minutes doing my sales calls,” or “I want to spend an hour with my family without distraction,” whatever the case might be, the goal is to do that thing, whatever it is that you put on your calendar for as long as you said you would, without distraction. That’s it. That’s all you have to do.

Work on that thing without distraction for as long as you said you would. It doesn’t matter if you finish. Why? Unlike the to-do-list methodology, in which people say, “Okay, finish this, finish that,” that’s what to-do lists are full of things you want to finish, the output.

What this technique makes you focus on is the input. The output is the task, the thing you want to have done. The input is two things: time and attention. By just prioritizing the input, the time and the attention, it turns out, people who use this methodology finish more. Believe it or not, people who don’t focus on finishing actually complete more than the to-do lists people. Why?

Here’s what happens to the typical to-do list user. This is what used to happen to me all the time. I’d work on a task for five minutes and then, “Oh, I got to check that thing. Let me just do that real quick before I forget.” Now I got to check email, now there’s a tap on the shoulder, and I got to do this real quick. And then, “Oh, wait, what was I working on again? Okay, I’m going to get back to that 20 minutes, 30 minutes, maybe an hour later.” Of course, we know it takes you about 20 minutes to get back into that task.

Your whole day is spent just getting through these reactive work tasks as opposed to truly reflecting on the task at hand, as opposed to people who are “indistractable.” When they work on that task and only that task without distraction, they can determine how much they accomplished in that unit of time.

I can say to myself, “Okay, I needed to make 100 sales calls. And I got through in 30 minutes, I got through 10.” Or, “I need to make a slide presentation for a client, and the slide presentation is going to be about 30 slides long, and I got through about three.” Okay, that means about 10% of the task was completed in that time box. And now, I can extrapolate how much time that task will take. Now, I’m freeing myself from the planning fallacy, which plagues people who use the to-do lists.

They don’t ever figure out how long tasks take, so there’s no feedback loop. Whereas with a timebox schedule, you learn over time. “Okay, this task takes me about XYZ minutes. I’m going to put that time in my calendar so that I can meet the deadline,” as opposed to what most people do. What I used to do is procrastinate, delay, distract, and then, right before the deadline, work like crazy. We know what happens, and our work output severely suffers.

Dangerous distractions trick you into prioritizing urgent and easy tasks, while neglecting hard and important work. Share on XYeah. This reminds me of what I learned from reading Cal Newport’s book, Deep Work. I interviewed him on Get Yourself Optimized, a great interview. There’s this concept I learned from him and from his work called attention residue. If you’re task-switching throughout the day, you not only lower your productivity while you are at work, but you also carry that home. Part of your brain is occupied with some of these other tasks. It takes, I think, at least 20 minutes for that other thing or things that you were working on to clear and for you to be fully present.

Yeah, absolutely.

This is a funny thing that popped into my mind, related to the whole to-do list thing. I read some books to my three-year-old son that are cute. They’re The Frog and Toad from 1972. It’s an old book series. One of the books is called Frog and Toad Together. And my favorite little story from that book is A List. That’s the name of it.

It’s about Toad creating a to-do list. He writes on his to-do list, wakes up, gets out of bed, brushes his teeth, eats breakfast, and so forth. He’s crossing these things out as he’s going through his day. Then he gets to Frog’s house, and he’s got the list in his pocket, and they go for a walk, and then he crosses out to go for a walk with Frog. As he’s crossing that out, the wind takes the list and blows it away.

Work can be separated into two types: reactive work and reflective work.

He becomes powerless to get anything done the rest of the day. He won’t even budge, but the face is after the list. He can’t catch it and comes back until it’s like, “I can’t remember what my next thing on the list is, so I’m going to just sit here.”

Finally, at the end of the day, Frog says, “Okay, let’s just go to sleep without even going home.” Toad’s like, “That was the last thing on my list.” He writes it on the sand with a stick. Go to sleep, and then cross out, and then they go to sleep. That just shows how you give your power away to to-do lists. It’s not empowering; it’s actually disempowering.

Yeah. It’s interesting how Toad needs to be told what to do with his time, and he’s powerless unless he’s told through a list what to do. That was written a long time ago before email. I would argue that most of us, most workers these days, are toads, but we don’t use to-do lists. Most of us are checking our email inboxes.

“I don’t know what to do right now. What do I do? Somebody, tell me what to do. Okay, let me just check my email. An email will tell me what to do.” And that is a massive mistake. That’s a form of what we call reactive work. Work can be separated into two types of work.

We have reactive work and reflective work. Reactive work is reacting to emails, reacting to messages, and reacting to notifications, and that’s part of everybody’s day. Of course, it’s going to be part of your day. The problem is that people can get habituated to responding to all that reactive work, and they get very comfortable there because thinking is hard work.

Thinking is typically the hardest part of a white-collar worker’s job. What we get paid to do is come up with novel ideas for heart problems. That is the definition of white-collar work. What most people unfortunately do is complain about getting distracted all day, but they make no time for reflective work. Reflective work is the kind of work you can only do without distraction. Planning, strategizing, being creative, and thinking requires planning time for reflective work.

As opposed to being like Toad and saying, “What do I do? Let me check my email because I don’t want to think for myself.” All Toad had to do was sit down for a second and say, “Well, wait a minute, what do I want to do with my time? And what’s important to me?” This is why we have to start with our values, by the way.

For the workplace, when we make that time for reflective work, even thirty minutes, that’s fine. Forty-five minutes, maybe an hour of your day, maybe more, you’ve got to put in the time for reflective work, or else you’ll find yourself running fast in the wrong direction.

Yeah, that’s so good. I needed these reminders. I know that I can’t let things like my email dictate my day. That’s somebody else’s priorities, and those aren’t my priorities. I also get caught up in bad habits, so thank you for the reminder.

I want you to remember we’re all part of this club. I wrote this book. Why do you think it took me five years to write this book? Because I kept getting distracted. I wrote this book for me more than anyone else. It wasn’t until I stopped and looked at these techniques and the research.

Reflective work is the kind of work you can only do without distraction. Planning, strategizing, being creative, and thinking requires planning time for reflective work.

I started from first principles because the first thing I did was read all the books on this topic, and all the books out there tell you the same thing: “It’s technology’s fault. Stop using so much technology.” I don’t agree. This is where Cal Newport and I have some disagreements. I think he’s great. I like a lot of what he says.

We agree on timeboxing, and it’s one of them. But his claims around how technology is a source of the problem, I really think it’s about how we use these technologies. I don’t want people to be Luddites.

It’s easy for a tenured professor to say, “Stop using social media.” Cal doesn’t use social media. Thanks a lot, but that’s something only a tenured professor can say for most people. If you’re a social media manager, how do you stop using social media? You can’t. You have to learn how to use this stuff in a way that serves you rather than hurts you.

We need to stop blaming that technology, realizing that that technology is very powerful and is designed to hook you, no doubt about it. Again, I wrote the book Hooked. I know all their tricks. But the part lost in this translation is that we wait for someone to fix this for us. I’m here to tell people you are far more powerful in these technologies. You just have to take some small steps to put them into place.

Good stuff, indeed. All right, let’s move to a marketing conversation now. I would love to unpack how you’ve built such an incredible and credible personal brand.

You’re speaking to Mindvalley’s audience. You’ve got a quest published there. You’ve done just some incredible personal brand stuff that I’d love to dive into a bit more. Also, I’m really impressed with the kinds of partnerships and relationships that you have from a marketing and reach perspective. Let’s talk about that.

Thanks. I appreciate it. I wish I could tell you it was planned. I can tell you the steps I took to get there, but it was a random walk. If there’s one thing that has helped me in my writing career, I always follow this mantra of following my curiosity. That’s always been my North Star. “What am I curious about?”

That Dorothy Parker quote, “The cure for boredom is curiosity. There is no cure for curiosity,” is such a motivator to me, just answering my questions. This is something I wrote about in my first book, Hooked, around variable rewards. How do we know intermittent reinforcement? This comes out of the work of B.F. Skinner—everyone who’s taken a Psych 101 class remembers B.F. Skinner—where he did these experiments on intermittent rewards.

What keeps us engaged, whether with a slot machine, watching sports on TV, or the news, all these things have an element of variability. Knowing that what I try and pursue in my life is those unanswered questions. For me, the variable reward is looking for the answers.

I don’t write books because I have the answer. I write books because I’m looking for the answer. I think certain readers really appreciate that. All my books are not only full of anecdotes, and of course, these techniques work for me personally, but peer-reviewed studies also back them.

There are 30 pages of citations in each of my books to peer-reviewed journals. I don’t like the books that are just like, “Oh, this worked for me, so it’s going to work for you.” That’s nice, but I want to see the studies too.

Following my curiosity has always been my path with all my writing. I try to write to solve my problems. When I don’t see books that solve those problems well, then every five years or so, I need to find the answer by myself. Thankfully, there are many problems to solve, so I never run out of material.

What would be something that, when you followed your curiosity, something quite surprising happened? Looking backward, you can connect the dots and say, “Yeah, that was totally meant to be,” but at the time, it just caught you by surprise.

The whole idea of becoming a published author, I started two tech companies. After the second one was acquired, I decided to take a break and look for what I would do next. Part of that was realizing the importance of habits.

This was back in 2012. Remember, the iPhone was only four years old at that point. I remember looking at the tech landscape. Both my previous companies were in the tech landscape. I realized that as the interface shrink.

We need to stop blaming that technology, realizing that that technology is very powerful and is designed to hook you.

As we went from desktops with big screens to laptops with slightly smaller screens, to mobile devices, and now wearable devices like the Apple Watch, and even more recently, the screen has all but disappeared. If you think about Amazon Alexa with these voice interface devices, the screen has completely disappeared. What that means is that as the screen shrank and then finally disappeared, habits became increasingly important.

For example, take on the phone. If you don’t exist on someone’s home screen, and they don’t have a habit, you don’t exist because there’s less real estate for those external triggers to tell people what to do. When we used to have huge monitors on our desks, you could ping and ding people to remind them to do something with external triggers. As the interface shrank and disappeared, there is much less space for those external triggers to give people information about what to do next, which means you must build a habit.

I wanted to figure out, “If I know habits are important, how do I build habits?” I just didn’t see that book on the shelf. I looked for it, but I couldn’t find that book. I decided to do research into it.

First, I started blogging about it, not thinking I would write a book about it, but just blogging for myself. Then, one of my professors at Stanford saw one of my blog posts, and he liked the model. He invited me to teach a class with him at Stanford. He gave me carte blanche to teach the Hooked model. That became a class at Stanford and later at the design school at the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design.

That whole process strings together like a good story and looks like it was planned out, but none of it was. Of course, the transition to “indistractable” was because I got so busy with consulting work, speaking opportunities, and investing, using the Hooked methodology that I was so busy. I didn’t have time to do what made me successful in the first place, which was writing. I was getting distracted from my writing, which I enjoyed and made me successful.

That’s why I wanted to write Indistractable to figure out, “Wait a minute, what happened here? I’m not doing what I wanted to do with my time and attention.” One thing led to the other by happenstance more than a plan.

How did you end up doing a quest for Mindvalley?

Vishen just reached out. He saw my material somewhere, and I don’t even know where. He just emailed me and said, “What do you think about doing an “indistractable” quest together?”

Awesome. Are you familiar with Mindvalley’s other quests and other Mindvalley subject matter experts?

A few. I know Jim Kiwk does one over there. There’s a life book that I’ve seen there. Do you use it a lot?

I’m a Mindvalley Pro member. I have gone through some of your courses. I haven’t completed it, I have to tell you. I did get distracted quite a lot. I like consuming online courses, books, etc., but I don’t tend to finish them.

Following my curiosity has always been my path with all my writing. I write to solve my problems.

I have to share this because it was such a profound thing I learned a couple of weeks ago. It’s called The Spiritual Flywheel. I learned it from David Ghiyam, who is co-founder of MaryRuth Organics, which has 25 million customers. It’s huge. It’s really successful.

He’s also a Kabbalah teacher. He was one of my Kabbalah teachers when I was living in L.A. In this prosperity mastery course, he explained the spiritual flywheel, which relates very much to some of the stuff we’ve been talking about.

He said that if you get 95% of the way complete with a project, but you’re not fully complete, it’s only 95% of the way, even 99% of the way there, you would get 95 units of energy. You would receive 95 units of light for that work, but you wouldn’t get to the finish line yet, so you wouldn’t get all of the units of energy. While there’s not just giving units of energy left to complete the project, you’ll get 10,000 units of energy by going that last 5% or 1% to finish it.

That just really stuck with me because, in the flywheel, you have to overcome the inertia to get the momentum going. But once the momentum goes with the flywheel, it just keeps going and going. You’ll get more projects completed with more energy. It releases all this potential energy and turns it into kinetic energy, into motion that will propel your life forward and give you so much light from above. It’s just so powerful. That is very relevant to what we’ve been talking about with distraction and traction.

Yeah, there is a euphoric feeling when you actually can see the thing that you said you were going to manifest. I would add to that. The difficulty of big projects is that you don’t get that feeling until the end, and that’s very difficult. If you ask folks why losing weight, saving money, starting a business, or writing a book is so difficult, it is that you have to work for so long before you see any payoff because people, again, are measuring themselves by the finishing, by the checking off the box.

That’s what we need to change. How do we change that? We change that by referring back to that system I told you about earlier of celebrating and measuring yourself, not on whether you finish the task, but did you do what you said you would do for as long as you said you would without distraction?

It’s such a killer insight. It’s not about finishing. It’s about celebrating the success of saying, “I was going to watch that online course for 30 minutes because that’s what was in my schedule, and I did it.” That’s what’s to be celebrated, those small wins.

Sometimes, I sit down at my desk, and I write maybe three words. I didn’t finish, but I celebrate the success that I had the discipline to sit down at my desk, be a professional author, and do my job, which is to sit here. My job isn’t to finish the book. It’s to write every day. If you can measure yourself based on that metric of “Did I do what I said I was going to do without distraction for as long as I said it would,” you will invariably and inevitably achieve those outcomes. But if you only wait for the outcome at the end, that’s very difficult.

Most people don’t have the wherewithal to sustain through difficult tasks. Easy tasks, fun tasks, that’s great. There’s this concept of flow, which is very nice, but it’s like work in Hollywood. Good work if you can get it. It’s very nice to have flow.

Csikszentmihalyi wrote his seminal book on Flow. Some people still sell courses and all kinds of stuff around this concept. He talks about basketball players, surfers, and people who are enjoying what they’re doing. That’s great. It’s easy to get into the flow and stuff I like doing. What about doing my taxes? How do I get in the flow of doing my taxes? I hate doing my taxes.

That kind of stuff you can’t measure yourself only by it is done because you’re going to procrastinate. You need to measure yourself by, “Hey, I worked on it for 15 minutes.” That’s great because if you work on it for 15 minutes, you’re going to get it done.

Reflective work is distraction-free. Plan time to reflect without interruption in order to think, strategize, and create. Share on XYeah, that reminds me of something I learned from Dr. Robert. Cialdini. Bob is how he goes. By the way, do you know who I’m talking about? He’s the author of Influence.

Yeah, of course.

He’s a master of persuasion. He wrote Influence, and then he wrote Pre-Suasion as a follow-up book. Anyway, he explained this recently in a Genius Network meeting. I’m part of Genius Network.

He said instead of congratulating your employee, your colleague, or your friend on their progress, if you congratulate them on their commitment, you will get so much more out of them because now, they’re forward-looking towards the outcome and the goal instead of looking in the rearview mirror at how far they’ve come.

Yeah, that’s absolutely right. We can apply that to our personal lives as well. One of my mantras is consistency over intensity in almost all things. When we think about intensity, people are like, “Okay, after New Year’s, I have a New Year’s resolution: ‘I’m going to lose weight, or I’m going to work my business.’”

They make these New Year’s resolutions on January 1st. By February 1st, they’d forgotten about them because they were super intense as opposed to consistent, which is very aligned with Cialdini’s concepts here. It’s about how I can put in that effort consistently. That commitment over the long term is really how we achieve everything worth having in life.

What other partnerships are you cooking up, or do you have besides the Mindvalley one?

There’s always something in the Hopper, but we’ll see what comes to fruition. I’ve got a few book ideas I’m working on. It’s too early to say at this point. I’m mostly focused on my own curiosities. That’s still my mantra.

I’ve got a few different book projects in the Hopper right now. One is about to get birthed. It’s the fourth edition of The Art of SEO, so that’s great. It’s not going to be a full 1000 pages like the last edition. It was 994 pages. It’s funny how fewer books sell when you make the book even bigger with each edition. This one’s less daunting.

The things I’m most passionate about, talking about curiosity, are the book projects that relate to spirituality and personal development. For example, I’m working on a children’s book. I’m working on a memoir about awakenings and living in a friendly universe. It’s fun to birth amazing passion projects and turn them into something.

Consistency over intensity.

Yeah, fantastic. With your SEO work, do you have any predictions about how LLMs will change the future of SEO?

For sure. We have a chapter in the new edition all about generative AI and how you can utilize it for SEO, everything from grouping keywords. You don’t even have to give it the categories, and it will just come up with the categories for you. And it’s a really good first draft to write content, even to come up with code. You can tell it things relating to Hreflang tags, and it will generate those for you.

It’s a powerful tool for that work, but there’s also the question of whether LLMs will put my traditional search out of business. My take on that is no. My co-author is also similar because it’s not that LLMs replace search. You still have to get this massive repository of information. Somebody has to get to your near and far website and read that blog post.

I don’t want an LLM to go in between to try and summarize your brilliance and get it wrong because these LLMs just make stuff up, the hallucinations. You have to be very careful about overly trusting these tools. People will still want to get from point A to point B in the most efficient way possible. That means Google is not going away, or they’re not replacing traditional search with Bard, SGE, or anything anytime soon.

Yeah. I do think that there will likely be certain types of searches that will make sense not to search on Google. For example, my daughter had a homework assignment in her world history class, something like, “How did the Ottoman Empire resist technological advancement and compare that to the Luddite movement?” She tried to type something like that into Google, and she spent forever looking for an answer, but she couldn’t find the answer. Essentially, I’m googling something like that.

She typed it into ChatGPT, and it spits out a beautiful answer. It may not be accurate. We actually had to ask it: “Please cite sources.” And then it did provide sources, which we could then link back to and be like, “Okay, that makes sense.”

That’s a different kind of search, though. Do you see that search?

It’s a question.

It’s a prompt that leads to a response that, after your follow-up request, gives you citations, which are essentially search results.

Right. It’s interesting that I do think that that will change the game for certain types of search results. There will be a layer. The UX won’t be a bunch of blue links on a page, which I think will be primitive in a few years. It’ll be asking an agent to find you the best source and then send it to you. That gives those guys a tremendous amount of power because now they’re just recommending one or two, not a user-scrollable page.

Yeah. You’re absolutely going to need to have a personal agent, your own trusted AI representing you, and having access to all this profile information, all this repository of your own data so that it can act on your behalf, rather than relying on Google or any other big tech company to make these decisions for you around what is the best thing to surface and present to you.

Yeah. Do you think that’s where it’s all going? Are we all going to have Her like the movie?

Yeah, absolutely. There’s no doubt about that.

Yeah, I can see that.

Interesting times ahead, right?

Yeah, it sure is. It’s amazing at the same time. These times of dramatic technological change always cause moral panics and fear, but it’s also important to keep our wits about us and ask, “Wait a minute, how much good can this do?” It’s a tremendous amount of good.

I saw this study recently about how an LLM is much better at bedside manner than doctors. Doctors are really bad at giving bedside manners. If they’ve just read the script from this LLM, they could do a much better job treating their patients. That’s just the tip of the iceberg. That’s just more of a customer experience-type role. But there’s so much these LLMs are doing for us that I think goes unreported because we’re so scared of AI taking over the world.

To look at where we’re at now is impressive. As you said, there are these LLMs figuring out all things in relation to health, early detection of diseases, and all sorts of stuff. But we got to skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it’s at now. Even in just two years, the landscape is going to be completely different.

I remember this as a prediction or analysis from Ray Kurzweil, where he said that the last 100 years of technology advanced at today’s rate of change, which is much faster now than it was 100 years ago. The last 100 years would fit into the next 20 years. But because it’s going to continue to advance, then it would only fit into the next 12. A hundred years ago, people would think you were insane if you described the kinds of technologies. It would sound like science fiction or fantasy. Imagine that in 12 years from now, it’s just mind-boggling.

Yeah, I agree, but I don’t think it’s going to change as much as people think. If you think about certain industries, they have not budged an inch. We went from the Wright brothers to the moon in less than 100 years, but from the jumbo jet to now, nothing’s happened. Aviation hasn’t changed much at all.

I got my pilot’s license. My father was a pilot. I got my pilot’s license back in 1996. The airplanes that we fly today are Cessnas, just like they were. Many of them are still made in the 1970s and 1960s. We still fly them today, and nothing has changed.

We can reclaim our productivity by understanding that it stems not just from focus, but from the deliberate pursuit of measurable progression toward our goals. Share on X

By the way, not that we could not have changed. There could have been a massive change. We went to supersonic flight for passengers to travel, and then we went backward. Right now, there’s no Concorde anymore. This amazing achievement stalled out, and we didn’t go down that path because of regulation.

Not that regulation was bad. A lot of the regulation was very good, sound ordinances, and this and that, practicalities, and fuel costs, etc. But we also need to be wary that not everything is going to evolve at the same time. This 100-year change in 12 years is not going to be evenly spread. It’s going to happen only in some industries and not others.

Yeah. There’s going to be a great divide in who benefits from this. There’s a fantastic book by Neal Stephenson called The Diamond Age. Have you read it?

No.

I highly recommend it.

Yeah, what’s the gist?

It’s about the coming age of molecular nanotechnology, where these nanomachines can self-replicate. That will be a huge tectonic shift for society. The subtitle of the book is a young lady’s illustrated primer. She has a primer-like tablet type of device that is her best friend. It is super smart. It is helping her navigate through the world.

She’s an orphan or somehow ends up on her own. It helps her get out of different mortal dangers and things. It’s nanotechnology. It’s fascinating. I don’t want to give too much away, but I highly recommend you read that book because it will get you thinking so big and into what’s possible because this is coming up fast.

It’s exciting times but also, for some, terrifying because they see the universes as unfriendly. The dystopian futures they see in these sci-fi movies just feel like an inevitability. They just resign themselves to some terrible Mad Max fate.

I understand and it’s hard to fight against, but we need to remember two things. (1) We have a negativity bias. We know that bad things draw our attention more than the promise of good things. That’s the first problem. That’s very dangerous because we only think about the crimes of commission versus omission.

We only think about the terrible things that happen, and we don’t think about all the good that could have happened if technology was around. We don’t count unsafe lives. We don’t count all the potential good because we don’t see it. It was an opportunity cost, not a real cost. That’s one big problem.

(2) Because of that negativity bias, there is an industrial complex of the media feeding into that. There is an industry of people who want you to be scared because they know that’s what gets attention. That’s what gets eyeballs. The first rule of journalism is if it bleeds, it leads.

The beauty of the human race and our civilization is that we adapt, even when there is bad.

There’s a whole industry of people who want to scare the crap out of you, and that’s very dangerous. Nobody tells you that, “Hey, there weren’t any plane crashes again today.” That doesn’t make headline news. Only the big fiery crashes do. The beauty of the human race and our civilization is that we adapt, even when there is bad.

Paul Virilio said, “When you invent the ship, you invent the shipwreck.” But we didn’t stop sailing ships, and we made ships better. We made them safer, not by not sailing them, but by improving them through technology. That’s what makes the chance of living better.

It’s very hard to keep your wits about you in this age when everybody’s telling you about fear, loathing, and all the disasters to come. Of course, Hollywood feeds into this, and the media feeds into this. By and large, I’m pretty optimistic. I’m sure there are going to be some disasters, 100% there will be disasters, but there will also be a heck of a lot of good done from all this.

Yeah, for sure. Stay positive. Things are looking up. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy, I think, the way the universe works. Anyway, I know we’re out of time. If our listener or viewer wants to learn more from you, of course, reading your books, both of them, but especially Indistractable, if they want to follow your blog or take your courses, where should we send them?

Measure progress by your commitment, not by your past achievements. Look forward to reach your goals. Share on XMy blog is nirandfar.com. My first book is called Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, and my second book is Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life.

Awesome. Thank you so much, Nir. This was a lot of fun. You’re such a light in the world, so keep doing what you’re doing.

I appreciate it. Thank you so much. Great to be here.

Thank you, listener. Be a light in the world, and we’ll catch you in the next episode. I’m your host, Stephan Spencer, signing off.

Important Links

Connect with Nir Eyal

Apps and Tools

Articles/Newsletters

Books

Businesses/Organizations

Films

People

Previous Get Yourself Optimized Episodes

YouTube Videos

Your Checklist of Actions to Take

About Luke Storey

Nir Eyal writes, consults, and teaches about the intersection of psychology, technology, and business. The M.I.T. Technology Review dubbed Nir, “The Prophet of Habit-Forming Technology.” Nir founded two tech companies since 2003 and has taught at the Stanford Graduate School of Business and the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford. He is the author of the bestselling books Hooked and Indistractable. In addition to blogging at NirAndFar.com, Nir’s writing has been featured in The Harvard Business Review, TechCrunch, and Psychology Today.

Nir Eyal writes, consults, and teaches about the intersection of psychology, technology, and business. The M.I.T. Technology Review dubbed Nir, “The Prophet of Habit-Forming Technology.” Nir founded two tech companies since 2003 and has taught at the Stanford Graduate School of Business and the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford. He is the author of the bestselling books Hooked and Indistractable. In addition to blogging at NirAndFar.com, Nir’s writing has been featured in The Harvard Business Review, TechCrunch, and Psychology Today.

Leave a Reply