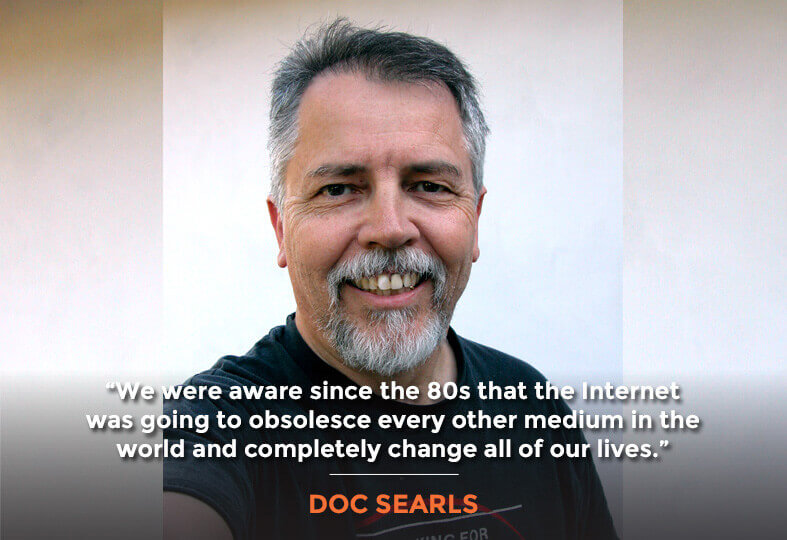

David “Doc” Searls is an American journalist, columnist, and widely-read blogger. He is a co-author of The Cluetrain Manifesto, author of The Intention Economy: When Customers Take Charge, Editor-in-Chief of Linux Journal, a fellow at the Center for Information Technology & Society (CITS) at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and an alumnus fellow of the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University.

In today’s episode, Doc dives into data rights and how we got to where we are today. He admits he used to be a cyber utopian, but now he sees the digital world for what it truly is–a world without gravity. Still, he remains optimistic about the distant future of digital marketing and consumer privacy.

We talk about the role of AI in data rights. We also discuss the concept of open source software development, a topic near and dear to Doc’s heart as the editor-in-chief of Linux Journal. As Doc says, “The internet belongs to us because we invented it.” You won’t want to miss this fascinating episode about the fight for individual data rights.

In this Episode

- [00:28] – Stephan introduces David “Doc” Searls, an American journalist, columnist, and widely read blogger. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Linux Journal, a fellow at the Center for Information Technology & Society (CITS) at the University of California, and an alumnus fellow of the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University.

- [04:55] – The reason behind the name The Cluetrain Manifesto.

- [09:27] – Doc shares about Customer Commons, a non-profit created out of ProjectVRM at the Berkman Klein Center.

- [13:08] – Doc explores the idea of a standardized loyalty program customers can use for companies they interact with.

- [16:14] – Doc talks about Marshall McLuhan, Media Studies inventor, and his one-liner, “We shape our tools, then our tools shape us.”

- [21:52] – Doc shares his thoughts about artificial intelligence.

- [26:56] – The problem with the current initiatives aimed at providing compensation for data consumers willingly provide.

- [31:39] – Read about The Cluetrain Manifesto website and look at the new clues. Grab a copy of The Intention Economy, and take a look at ProjectVRM and join the list.

Transcript

Doc, it’s so great to have you on the show.

It’s great to be here too. I should add to that long list of universities that never would have let me in as a student, that I’m also a visiting scholar, which is half true. I’m visiting Indiana University for the next year while we’re working on a lot of what we’re talking about.

Amazing. All right. Let’s first start by talking about The Cluetrain Manifesto because, at least for me, that really put you on the map. I hadn’t heard of you before that and it was such a monumental, pivotal work back in those early days, 22 years ago of the development of the internet and internet marketing.

I think it has shaped how things have evolved to some degree. I would like to have said it would have made more of a difference. People are still doing all sorts of crazy marketing things that don’t help our consumers, but we’ll talk more about that in a minute. Cluetrain Manifesto, how did that come about, and how did that change how the internet and marketing developed?

The Cluetrain Manifesto was written by four technical guys, one of whom was really technical—that was Rick Levine. Chris Locke, David Weinberger, and I were and remain writers, primarily journalists, but we’re also doing work for companies. At the time, Chris was working for IBM, David, I forget who David was working for, and I was working at Linux Journal. I was an editor for Linux Journal.

We were all enthusiasts of the internet. We had all been aware from the 1980s of what the potential of the internet was. That it was going to obsolesce pretty much every other medium in the world, completely change all of our lives, and most importantly, actually liberate all of us as human beings to play a much more active role in the commercial world, as well as the creative world, and every world that we interacted with.

We were all enthusiasts of the internet.

To a large degree, a lot of that’s come true, but the important thing is that we were addressing The Cluetrain Manifesto to companies that didn’t really get the internet, that didn’t really get what the internet was about. We were just involved in conversations with each other, a lot of it on the phone.

It created this little cabal of guys who just got on the phone, carped about the world with each other, and told stories about how clueless marketing was. We talked about how we accepted or did not have clients for our marketing services. My marketing philosophy that I share with potential clients; it’s kind of a marketing logic. The first condition is markets are conversations, the second is conversation is fire, and the third is that marketing is, therefore, arson if it’s done right. If you are somebody who sets fires, I’m your guy, and if not, go write press releases for yourself. Chris said—I think it was Chris, it may have been David—well, let’s test that out. Let’s test that theory. Let’s set a fire.

We decided to put up a website that pretty much said everything that we’ve been talking about to each other. I called it The Cluetrain Manifesto for three reasons. One was, there’s an old Silicon Valley epitaph, something of a joke that the Cluetrain stopped there four times a day for 10 years and they never took delivery.

We were aware since the 80s that the Internet was going to obsolesce every other medium in the world and completely change all of our lives. Share on XSpecifically, that was about Apple at the time. Steve Jobs had just come back and it was truly a clueless company for a long time, certainly not anymore. One of us said, is that domain taken, Cluetrain? I looked and it wasn’t, and I bought it for $75. That was the entire dialogue that caused The Cluetrain Manifesto to get the name that it has.

We called it a manifesto because it worked for Marx and we had 95 theses because that worked for Luther. Those were market-tested, we thought so. We use those. A lot of the 95 theses were packing material, quite frankly.

The really important one was the one that Chris shared with the rest of us, and he shared with us a little graphic, he sent it out by email. It said, “We are not seats or eyeballs or end-users or consumers. We are human beings—and our reach exceeds your grasp. Deal with it.” We liked that so much that we’ve made that the one clue you want to get this year, which of course is 22 years ago.

Our reach does not exceed the grasp of the marketers of the world.

It’s actually one clue that is not true as of today. We are still seats, eyeballs, end-users, and consumers. Our reach does not exceed the grasp of the marketers of the world.

If anything, it has made the world a lot worse, not because they follow the Cluetrain, but maybe in some ways because they did. Because they thought, well, we could do conversation now. Let’s do it by intercepting people personally. We’ll follow them around there as they go from website to website. We’ll use cookies to follow them and other tracking files, we’ll accumulate lots of data about them, and then we’ll market at them accordingly.

By the way, that’s not exactly what’s made Google rich, and to a lesser extent, it isn’t what made Facebook rich either, even though they’re the target of a great deal of ire at this point. Google makes most of its money actually still from search advertising, which doesn’t even require tracking for the most part. But still, tracking has become so normative that it caused the GDPR, it caused the CCPA in California.

It has made the world infinitely worse as an experience online. It’s eliminated whatever little privacy we had just given the respect human beings give to each other. Marketing has become by far the biggest violator of privacy in human history. For what it’s worth, I’ve spent a lot of the last 22 years, since then—especially, in the last 10 years or so—fighting that personally.

I’ve written an enormous amount about that. If you go to my website at doc.searls.com—that’s a short link toward what’s a much too long URL for my blog that’s still at Harvard—you’ll see something called People vs. Adtech. There are 142 pieces since 2008 that I’ve written about this. I pretty much stopped. I’ve stopped because I actually want to make Cluetrain come true, and I want to make what I wrote about in a subsequent book called The Intention Economy: When Customers Take Charge.

What happens when customers do take charge, which is what that first clue in Cluetrain actually said? When we are in charge of our own lives online, and not just so we can give ourselves actual privacy. Like we have in the physical world, you notice that both of us are wearing clothes. That’s privacy technology. We have that here in the physical world.

We don’t have it online yet. We don’t have clothing and shelter. We shouldn’t have to rely on government regulation to give it to us. We should just have it because it’s built into the tools that we use. It’s built into how we interact with each other.

If we go to a website or we engage a service online, we don’t have to think about whether or not we have privacy. It’s just there because we’ve taken the trouble to put on a shirt and some pants or the digital equivalents of those, which are also by the way still uninvented. We’ve got an uphill climb on that one.

The main idea with The Intention Economy is that rather than having marketers constantly guessing mostly based on surveillance at what we might want, and making a really gigantic category era, which is that we are in the market for something at all times when in fact we’re not. You and I are talking to each other right now. We’re not busy wanting anything other than to have a conversation. We’re not busy putting ourselves in the market for anything.

We own things 100% of the time, but we’re looking for things, a very small percentage of the time. The assumption behind most direct marketing—which is what advertising has become, it used to be advertising, now it’s direct marketing—is that we’re in the market. We want to buy something at all times, it’s not the case.

When we do, we should have better ways of expressing our intentions than what companies are guessing at because they think they know us or their robots think they know us. If I want a stroller for twins downtown in the next two hours, it should be able to express that in a way that the market can hear and respond to in a way that respects my privacy and works.

We actually have some tech for this. It’s the Customer Commons, a nonprofit that we created out of the ProjectVRM at the Berkman Klein Center now at Harvard, which is still happening. We have a list of about 600 people on that, but we created this nonprofit Customer Commons. We have some tech now. That’s what we’re going to try out in Bloomington, Indiana in the next few months and see how it goes.

It’s very alpha to beta right now, but it’s going to happen. It will involve lots of different categories—I want a car, I want a babysitter, I want this, I want that. Be able to do this anonymously, then form real relationships after that with vendors that are welcoming of that, and can understand real loyalty rather than the kind that we have right now.

How does this relate to the concept of The Cathedral & the Bazaar?

The Cathedral and the Bazaar is this wonderful book written by Eric Raymond, about the same time this Cluetrain came out. I would say, by the way, it was great and more influential. We’re talking about open source today because Eric personally made it his business to promulgate that meme.

The term open source was not used except by the military before 1998, and a bunch of geeks including him, got together in early ‘98 and decided, we’re not talking about free software anymore, we’re talking about open source, and not even here’s why. That’s what we’re going to do.

I was enlisted in that cause and promulgated it as an editor for Linux Journal. The important part about it is that his metaphor, The Cathedral and the Bazaar, was really applying to software development. Rather than having big companies that cathedrals in their closed source proprietary way, writing all software for their purposes and secondarily for those of their employees, customers, and consumers (there’s a difference). That software would be developed out in the bazaar, out in the open marketplace by individuals working together. That’s what we have now.

Open source is now an essential part of the way that software development works. Companies will hire open source developers knowing they’re going to work on that code for the world and not just for the company itself, and that code is correctable by anybody who’s qualified, participates, and knows what they’re doing. There’s a meritocracy involved.

Open source is now an essential part of the way that software development works.

Its relevance to the marketplace and the Cluetrain is that out here in the marketplace, we should have full agency. We should be able to participate in the way markets work, and not just be targets to be acquired, controlled, managed, locked in, which is the language that marketing still uses to talk about us. That we should have our own means to interact at scale.

For example, not just when we say we’re ready to buy something, but we’re ready to be loyal. For example, I’m very, very loyal to Trader Joe’s and to Peet’s Coffee. Those are two things. I told my wife and she said, “I’d like to move to Santa Barbara from the Bay Area.” I said, “My only condition for that is that there is a Peet’s coffee there, and secondarily, we’ll have better connectivity that we got in the Bay Area,” which is true. There was actually better connectivity available, and a Peet’s had just opened at that time.

Peet’s has a loyalty program that frankly is a pain in the ass. It’s where you have to get your phone out, you’ll have to hold it up to the QR code reader, and then you get promotional materials and a bunch of other stuff. It slows things down at the cash register. It’s a pain in the ass for everybody on both sides.

Data rights are the new civil rights. Share on XWhat does it give them? They’re a great store, they have loyalty already. When there’s a Starbucks and a Peet’s, the Peet’s wins generally when it’s next door. People like coffee and not just large quantities of milk with coffee flavoring, they’re going to come to Peet’s, but they have this pain in the ass loyalty program.

What if not only would I be able to express loyalty in my own way, but a standard way that I can do it with every company I deal with? Loyalty looks like this—the customer reaches out, says these things, and provides these means where the company’s product could be constantly improved because they’re getting real caring feedback and ideas from customers.

An idea I would have for Peet’s is what I got from one of their managers. Well, the best-tasting thing here is their Cortado. The Cortado is an equal mix of espresso and milk, but preferably, half and half. Try it sometime. It’s under the cash register, you can’t see it, it’s not up on the wall. They used to have one called Traditional Cappuccino, which by the way, is the same thing but more expensive. That’s still on the cash register.

I would like to suggest to Peet’s, this something suggested by one of your managers would actually be good in all of your stores. If you’ve got an app, have the menu on the app, don’t just have it on the wall. If you use the app with the QR code, do it in a way you just come in, you scan the QR code, and it’s automatically in there. They have your name, they have what you’d like.

Instead, this is a really kludgy system that’s a one-off that they bought from some company that’s an arms dealer to retailers, and isn’t a shared experience in common like you can have the same thing with Starbucks. You have the same thing with the grocery store when you come in.

What aisle are the canned beans on? What aisle is the yeast? I don’t know. Scan this, it’s in the store. There’s some standard-based way that stores appear on an app that you carry into the store, you scan with the QR code, and now you know where stuff is. Instead of being the promotional thing that we have now.

If you start rethinking markets from the customer side and you start thinking of the customer having scale across all the retailers that they deal with or all the services that they deal with, what does the world start to look like?

The internet provides this. The internet is essentially a peer-to-peer system. It’s not just the latest version of the same old industrial system where large companies dominate entire markets and get their own scale.

The internet is essentially a peer-to-peer system.

How did companies and the industrial complex go wrong? Everyone is so excited about these two books, The Cluetrain Manifesto, The Cathedral and the Bazaar. Now here we are 20 some years later. It’s a mess and it doesn’t feel like consumers have real data rights. It’s like data rights is the new version of civil rights. We don’t have it and it’s the companies in charge. As you said, it’s not in our best interest as the end user.

It’s interesting. That’s a really good way of putting it, data rights as the new civil rights. The civil rights don’t go away. I was involved in the civil rights movement in the 1960s, in Greensboro, North Carolina 10,000 years ago. It’s a bigger issue now than it ever was, but data rights are gigantic.

I think the answer is one provided by Marshall McLuhan, who really invented Media Studies back in the ‘50s and ‘60s. He says every new medium and every new technology—he didn’t make a distinction between the two really—changes us completely. It changes us. One of his one-liners and one attributed to him is that, “We shape our tools, then our tools shape us.”

He saw computers coming, and he saw it implicit in satellite communication back around 1960 when he coined the term “global village.” We’re in that global village now. Digital technology has not only shaped us, but with the internet, it puts us in a world where you and I are right now without distance. For that matter—I owe this metaphor to my wife, I was observing this stuff—without gravity.

The Internet is essentially a peer-to-peer system. It's not just the latest version of the same old industrial system where large companies dominate entire markets. Share on XThe physical world is full of prepositions and prepositions give us location—over, under, around, through, besides. There are about 60 of those and that’s how we understand the world. We can’t get along without prepositions that locate us.

The only one that applies on the internet is with. You and I are with each other right now. When this is over, we’re not with each other, and it’s binary that way. We’re in different parts of the world, even if we’re a few blocks apart. Our gravity is looking straight down. But if you’re in Australia and I’m here, you’re upside down, but we don’t see that.

We’re in this world without distance. It’s like being weightless, and it’s taking us a long time to adapt. There’s a principle in technology that says what can be done will be done until we figure out what’s wrong with it and stop doing it. We did that with nuclear power, we’ve done that with stone tools, we’ve done it with guns, we’ve done it with machinery, all kinds of things.

We’re in this world without distance.

By the way, bad things will be done with good things at all times. McLuhan also wrote that every new medium works us over completely, and that’s basically what happened. The great optimism that The Cluetrain authors had—and we were called correctly cyber utopians. I think it will come true in the long run. But in the meantime, the stuff that works is over completely still manifests, and it’s too easy.

We designed web servers originally so everybody could have a web server. If I’m not mistaken, every Windows and Mac operating system in the ‘90s shipped with a web server. You could run a web server on your computer. Maybe they still do, I don’t know. Linux, which is in every clock for that matter, is a server-based operating system. Anybody can have one on their computer, but all of us should be able to be servers as well as clients.

Even the notion of client-server—I’ve been told, and it’s perhaps apocryphal—that it’s a euphemism for a slave master. It’s been called calf-cow. We’re always the calves going to the cows of websites for the milk of HTML and cookies. That master-slave relationship is one that the industrial system—which began in the mid-1800s when industry won the Industrial Revolution and has never left us—gave us because the imperatives of the industrial system are well understood. And they are very efficient, they work really well.

It’s a lot easier to put stuff in a cloud than it is to keep accumulating disk drives.

A big company could do a lot of things that a small company can’t do. We’re seeing this with the cloud. It’s a lot easier to put stuff in a cloud than it is just to keep accumulating disk drives. I’ve put up a blog post about this yesterday. There are 17 drives over there in the corner of my desk and half of them are dead. What do I do to backup? I’m having to put it in the cloud sooner or later. It’s a more efficient way of doing that.

I used to have a web server under my desk in the ‘90s, and I used to have my own mail server under my desk because I could buy static IP addresses. Try buying a static IP address now. It’s assumed, no, you don’t need one, nobody demands one. Well, there’s no way to do it.

Of course, internet connectivity was provisioned asymmetrically because it was assumed you’re going to want television, and you’re going to want to do nothing but download. They only publish download speeds rather than upload.

Interestingly, Spectrum—my provider here in New York—which was never better than 10 megabits up even though it was a half gig down, is now 80 up. I don’t know why it just suddenly is. Maybe because it knows we’re doing Zoom now.

The internet will not go away

Why not? They’re tired of the complaints, so they just crank up the upstream speed. My belief is they’re still in very early times right now. We’re going to be digital not only for a few decades, probably for the duration. For as long as we’re human, we’re not going to stop being digital.

The internet will not go away no matter how much companies or countries sphincter what it can do. It’s going to be with us for the duration. We’re going to be with each other whether we like it or not all over the world. We’re going to create and solve problems that way. We’ve just started on that. It’s a long journey.

While I’ve been young for a long time, I’m demographically old at this point. I’m not going to live to see it, but it is going to happen. I remain a cyber utopian about that. I’m optimistic.

I’m optimistic too. I’m curious what your thoughts are about AI and how personal agents or smart agents, the AI that knows more about you than perhaps your spouse? It’s searching on your behalf, curating all day long in the background, bringing stuff to your attention. Is that something that is ultimately for our highest good, or is that just going to be infiltrated by marketers and advertisers just like the internet is?

All the above. My wife—as you’re describing that—it’s like a perfect explanation. I’m pretty much calendar blind and clock blind. I’m calendar blind. I will make mistakes. If you asked, when is September 19, she’ll tell you it’s a Wednesday or whatever it is. She knows. She’s very, very observant, picks up lots of details, and runs both our calendars.

First of all, most AI is ML, it’s machine learning. I think real intelligence of the human sword is very tacit, it’s not explicit. Computers are explicit. Then philosopher Michael Polanyi made this distinction about 50 years ago and more than that. It’s a really important one, which what we know is mostly tacit.

We generally don’t know how we’ll end the sentences, we start remembering how we started the sentences we’re ending, but somehow say meaningful things anyway that (to some degree) come across with people at the other side. And they can’t repeat verbatim exactly what we said. That’s explicit.

The computer can repeat it exactly. This is being recorded, it could repeat it exactly. But the human being just gets meaning, the human being just wants meaning and knows what’s important and what’s not, and can’t say how or why. For us, they know no machine intelligence has replicated that or can.

That is a fundamental problem with artificial intelligence and pretty much all are fantasizing about it. However, as I look around here, for example, we can’t show you these, but I’ve got my bookshelves over here. There are hundreds of books there, and I’m going to take about half of them to Indiana next month. Which half would I want to take?

All of those I would love and by the way, the code exists for this. I could just scan the ISBN number on the back of those things. There’s some intelligence that can say this is machine learning at work. That’s an ISBN number, that is Too Big to Know by David Weinberger, and that is The Master Switch by Tim Wu. I could just look down the list and say, this one, not that one, this one, not that one.

Right now, I could take all those 18 drives I have over here—18 including the computer—and I could put a QR code on all of those. Then I can tell Western Digital, Nexstar, or Seagate, which makes some of those. Here’s my experience with these things. This one died, that one didn’t die, this one died then, this one didn’t die then.

Here’s some Grado headphones. These things sound fantastic, they really do. But the earphone part here, the rubber part rots after a while, I’d like another one. They last about two years. Automatically, give me one in another two years and I’ll pay $10 for it.

This is the kind of experience I can have as an individual human being that’d be really good for the companies to know, as I was saying earlier. But ML can be involved in that. I have doctors because I live in all these places—New York, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, and soon-to-be Bloomington, Indiana—and I have up here a pile of medical records that are in print. Some of them are xerox copies of faxes because the medical business likes to communicate by fax, ironically and disturbingly.

We can improve on that, but we can’t improve on it from the inside, we have to do it from the outside in. I would love to do ML and AI, whichever you prefer, on all that stuff. When did I have that hernia operation? When did I have my hip replaced? Where was that? Who is that doctor? I forget. That kind of stuff is really useful and financial stuff as well, but having marketers guess at that is just ludicrous actually.

We need capacities on our side that help us, and then we can go to the marketing functions of the world and say, here’s the stuff that you need to know or you might want to know with conditionalities we’ve attached to it that are good for you as well as for us. And that may not make you a honeypot for bad actors that want to grab everybody’s data in the world.

By the way, if it’s done in the right way, also leave you legally held harmless if there’s a lawsuit or something. All this stuff can be worked out. I would rather have a dumb agent before I have a smart agent. The dumb agent would be the one that says, as we had a few months ago, okay, we’re looking for a hybrid car that gets at least this miles per gallon. That doesn’t need a lot of repairs, that kind of thing. That’s a dumb agent that would do that. And then, if you want to get smart about it later, that’d be great.

It’d be really nice to have these new data rights that we really desperately need as consumers have that also compensate us. We can make the choices like, all right, I’m going to share this data about my hip replacement with you, but I want some compensation for that. I want a special discount on whatever that thing is that relates to my mobility or whatever.

There are five or ten different efforts right now going on toward exactly that. My problem with all of them is they all deal with the system as it now exists. And also, it assumes that my data has more value than it actually has. If you look at what Google or Facebook thinks my data is worth, it’s really not very much.

We humans invented the Internet, and it belongs to us. Share on XGetting compensated for that—fractions of pennies in most cases—just sets up yet another system within the existing marketing FICO system that could be gamed. I just rather, guys, I need this car. I need another hard drive. Right now, I would like a portable hard drive that’s at least 8 TB. I can’t find one.

I have a put on the marketplace right now, and my payback on that is I get the damn product I wanted, not that I got 4¢ for having said so to marketers that are going to spam me until the end of time. They can’t say otherwise because that’s what they prove they’ve been doing for the last 25 years.

I’d rather just build a whole new system that actually works for me, my way, and by me. I don’t mean, just be myself. I mean, everybody who’s a customer should have their own ways to express a need, express a preference, or express anything else that works at scale.

Everybody who’s a customer should have their own ways to express a preference.

It seems to me like we’re due for a new edition of The Cluetrain Manifesto because you guys just still don’t get it.

Actually, David Weinberger and I published one together. That’s just a website. It’s a page called New Clues, and it’s at Cluetrain.com/newclues or newclues.Cluetrain.com. I think both of those will work. That went out in 2015 and basically has to do with how we understand the internet. When people say, the internet wants me to do this or to do that, that’s like saying gravity wants me to do this or that, or food or the air wants me to do this and do that.

The internet is not Facebook, Google, Apple, and Twitter. The internet is the gravity that holds all those things together. It’s the rising tide that floats all boats. That’s what we were saying there. We also said, and this is a supposition on our part, which is that the internet is ours. The internet is not Google’s or Facebook’s.

The Internet belongs to us, and it’s like we invented it. Nature, God invented gravity and the planet, but we invented the damn internet and it’s ours. It’s a human invention, and it is also a genie that’s not going back into the bottle. TCP/IP as a protocol is too good at what it does, even though there are some that find fault with it.

The internet is the gravity that holds all those things together.

The profound insight that we should have a protocol, which is nothing more than manners among computers, that says these packets will find the best path to the other end. Any drop packets can be resent with complete agnosticism to who’s in the middle, and especially toward billing. If the phone companies and the cable companies, which would love to take credit for it, had built the internet in the first place, we wouldn’t have it, we’d have a billing system.

I worked for BT in the UK for a number of years as a consultant, as an outside guy. JP Rangaswami, who has been a great partner and a great many things. He’s almost like a fifth Beatle for The Cluetrain four. He was one of the first people that came to us that said, I love what you’re doing.

JP was the Chief Scientist at BT and hired me on. He said about BT, we are not a communications company. We are a billing company. Our core competency is billing, not communications. Not that they’re incompetent at communications, but billing is what they’re built for.

The government’s the same thing. If it had been up to the ITU, which is very much about the telcos and the governments, there would have been tariffs at the borders like we had in Europe, especially, and outside the US as well. We didn’t feel it as much. With cellular telephony, we don’t have it anymore because it turned out to be ludicrously inconvenient.

We designed web servers originally so everybody could have a web server. Share on XIf you were in Europe, I had friends that had this problem. You’re in Strasburg or wherever, and you’re in France, but you’re on a German cell. All of a sudden, you’re getting a gigantic bill for data usage. This is ridiculous.

That’s another problem with data as a fungible commodity. The internet’s a copy machine. It’s not. Thank you, Kevin Kelly, for that metaphor. It’s a copy machine. If you send me a file, you’ve got a copy of it. You and I are both recording this right now. We have copies. We’re making copies as we speak.

We’re out of time. But if our listener wants to learn more, read The Cluetrain Manifesto, and learn more from you, what would be the best place for them to go to?

The easiest thing is to look me up and look up Cluetrain. The weird thing about Cluetrain is the same website has been there since ‘99, and we’ve updated it with a few things. Look at new clues, even though it’s now more than six years old. It’s important stuff, I think.

Pick up a copy of The Intention Economy as well. An interesting thing, I wrote that in 2011, came out in 2012. All the companies I mentioned in it, for the most part, are dead, but the points are the same. If we rewrite it now, it’d be the same thing with the new companies mentioned. Take a look at ProjectVRM and join that list.

Awesome. All right, doc.searls.com and Cluetrain.com are two great sources of work. Thank you, Doc. This was great.

Thank you, Stephan. Really appreciate it.

Important Links

Your Checklist of Actions to Take

About Doc Searls

David “Doc” Searls is an American journalist, columnist, and a widely read blogger. He is a co-author of The Cluetrain Manifesto, author of The Intention Economy: When Customers Take Charge, Editor-in-Chief of Linux Journal, a fellow at the Center for Information Technology & Society (CITS) at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and an alumnus fellow (2006–2010) of the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University.

David “Doc” Searls is an American journalist, columnist, and a widely read blogger. He is a co-author of The Cluetrain Manifesto, author of The Intention Economy: When Customers Take Charge, Editor-in-Chief of Linux Journal, a fellow at the Center for Information Technology & Society (CITS) at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and an alumnus fellow (2006–2010) of the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University.

Leave a Reply